Histor-E

Each month, the Idaho State Historical Society releases a “Histor-E Lesson” along with an e-newsletter. Subscribe to Histor-E to get notified about upcoming events and programs, and other historical happenings across the agency.

CONTACT US

(208) 334-2682

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

This Month's Histor-E Lesson

Skinner Toll Road

Idaho became a magnet for ambitious prospectors in the mid-1800s. People from all over flocked to Clearwater, Boise Basin, and the Owyhees in search of gold. By 1862, significant lodes were discovered in Boise Basin, making it a top destination for placer miners virtually overnight. In 1863, Michael Jordan and his party of twenty-nine men and sixty horses left Boise Basin for Southwest Idaho’s Owyhee Mountains in pursuit of rumored deposits. They stumbled upon a gold-filled creek near the mountains, and after establishing camp, they named the creek after Jordan, which eventually led to the name of the surrounding valley and town.

The discovery of gold in the Owyhee Mountains in 1863 spurred the need for better transportation infrastructure. At the time, routes for packing out the yields of gold from mining towns like Ruby City and Silver City in the Owyhees and getting them to the mint in San Francisco were difficult, inefficient, and unreliable. From 1863 to 1865, transportation companies from Oregon and California worked on trails to the Owyhee mines, but despite the investments, their routes left a lot to be desired and, at times, were unusable. Silas Skinner, from the Isle of Man, saw an opportunity and formed two road companies to undertake the ambitious project of constructing a complete and navigable toll road through rugged terrain.

Skinner partnered with H.C. Laughlin and began construction on the project, repairing old roads and creating new ones, meanwhile overcoming natural obstacles such as hardened lava fields, steep gradients, and unpredictable weather with basic tools, manual labor, and oxen. Nearing completion in late December 1865, Skinner applied to the Idaho Territorial Legislature for franchises to operate two toll roads: one was for the existing Reynolds Creek Road he repaired, and the other was for a new road extending from Ruby City to the Oregon border via Jordan Creek. Skinner’s applications for toll road franchises were approved by the Third Session of the Idaho Territorial Legislature on January 3, 1866. Governor Lyon signed off on these franchises, allowing him to charge a toll on the Idaho portions of the road, and as the news spread, freighters eagerly anticipated the full opening of the road. In Sacramento, a train of one hundred horses, eight mules, eight yokes of cattle, thirty men, and twenty-five wagons capable of carrying 4500 to 6000 pounds each were prepared by April 1866 to head to Idaho. Skinner opened his highly anticipated toll route a few weeks later, in May 1866. By then, the road spanned approximately seventy miles from Silver City in the Owyhee Mountains down Jordan Creek to its junction with the Owyhee River at Duncan’s Ferry.

The toll road opened up transport to new arteries and provided a vital link to Chico, CA, for transport to the mint in San Francisco, significantly reducing travel times to and from the Owyhees. On the renovated Reynolds Road, tolls ranged from five cents per head for sheep and swine to a three-dollar toll for a four-horse team and one loaded wagon. Rates were approximately double on the newly constructed road. Skinner’s toll system funded road maintenance and improvements, essential for the road’s survival in harsh conditions under heavy use.

Skinner’s toll road boosted trade and economic growth in the region, fostering new stage stops, ranches, and settlements. The rapid development also led to conflicts with Native American tribes, prompting the establishment of military posts along the Idaho-Oregon border to protect settlers, including Camp Lyon. However, soldiers offered little protection and freighters would travel in companies of ten or more, camping in circles around their fire to protect themselves against raiders and outlaws.

Silas Skinner’s influence extended beyond road construction; he invested in mining and ranching, bolstering the region’s economic stability. As mining activity declined by the late 1870s, the road’s importance waned, and Silas sold off parts of the Skinner Toll Road. In 1878, after Owyhee County purchased much of the road in Idaho, the Skinners relocated to a new ranch further down the valley before moving to Napa Valley, CA for the remainder of Silas’ life. After Silas died in 1886, the Skinner family returned to Jordan Valley, where the family remains. The historic Skinner Rockhouse, built in 1872 and owned by the family since 1929, now operates as a coffee and ice cream shop, serving as a testament to their enduring presence and contributions to Jordan Valley.

The Skinner Toll Road’s legacy endures in tales of hardship and success from the Owyhee mining era, marking a lasting impact on Idaho’s economic and social fabric. Today, remnants of the road exist as segments of modern highways, local roads, work roads, mountain biking trails, and cattle grazing fields. Historical stations and structures remind modern visitors of its significance, preserving a piece of Idaho’s past.

Written by Noé Zepeda

http://skinnerfamilynw.org/history/skinner%20toll%20road.htm

https://skinnersrockhouse.com/

https://history.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/0427.pdf

Skinner Toll Road

Image: http://www.skinnerfamilynw.org/images/gallery/skinner%20map.jpg

Previous Histor-E Lessons

Who’s ready for a short history pop quiz?

What do the following Gem State campgrounds share in common? Here’s the list: Lake Walcott State Park near Rupert; Twin Creeks Campground just outside of North Fork in east central Idaho; Heyburn State Park, Idaho’s first state park, built on Lake Chatcolet north of Plummer; and finally, let’s throw in a series of smaller campgrounds along the banks of the South Fork of the Salmon River east of McCall.

Need a hint? Ok, consider the fact that all of these recreational sites are linked to one of the most successful federal programs ever created, an all-out effort designed to put hundreds of thousands of Americans back to work and, at the same time restore and improve millions of acres of forests and public lands across the country.

The fact is, each of these campgrounds, along with hundreds of other projects across the state, were built or improved thanks to the handiwork of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Better known as the CCC, this New Deal program launched by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933 was a response to a nation languishing in economic depression and the 1929 stock market crash. But the CCC had more practical ambitions, such as rejuvenating America’s natural resources that had been damaged by overcutting, overgrazing, soil depletion, farm closures and devastating wildfires.

As Idahoans gear up for a summer of camping, hiking, fishing, and exploring state parks and national forests, it seems timely to take a glimpse back in time and examine the CCC’s impact on the state’s abundant and enduring recreational resources. Whether it’s building campgrounds, fish hatcheries, or fire lookouts – many of which are rented out for lodging today – or constructing roads, trails, and bridges through forest lands, the CCC’s fingerprints are scattered all across Idaho’s recreational backcountry.

On Apr. 5, 1933, FDR signed an executive order creating the CCC. Leaders in Idaho, realizing the potential of the program, responded immediately. Within weeks of FDR’s action, Idaho Gov. C. Ben Ross dispatched two of his top officials to Washington, D.C., to negotiate the state’s involvement in the new program.

The first CCC camp arrived on the scene months later. On Jun. 6, Camp Prichard, located on the North Fork of the Clearwater River, became the first operational CCC camp in the state. Over the next ten years, more than 87,000 Americans between the ages of 18 and 25 who enrolled in the CCC would make Idaho their temporary home and job site. When the CCC ended its run, Idaho had the largest number of CCC camps per population, second only to California.

In many ways, it’s hard to imagine Idaho’s impressive inventory of campgrounds, parks, hiking trails, backcountry roads and other recreational infrastructure without the sweat, muscle of CCC laborers and the engineering savvy of the Corps’ officer class.

Here are a few facts to consider as part of the scope and impact of the program. The “CCC Boys” are credited with building thousands of miles of trails in the backcountry and hundreds of fire lookouts that, for decades, would play a vital role in helping fight wildfires. CCC crews built dozens of U.S. Forest Service ranger stations, some of which the agency rents to people looking for a unique backcountry lodging experience.

In 1935, a party of explorers, scientists, and documentarians sponsored by the National Geographic Society ventured down the Salmon River, marking one of the first public research expeditions into the Western wilderness. The explorers paid a visit to Camp French Creek, the base for CCC crews assigned to the challenging task of building a road between the river and the cliffs lining the banks. This project, which on paper was intended to but a path through the largest wilderness area in the lower 48 states, was ultimately shelved after leadership determined it was too costly and difficult. In north Idaho, CCC crews blasted the 415-foot Fishhook Tunnel through the Bitterroot Mountains near Avery.

The impact of the CCC also extends beyond recreation. Crews connected more than 3,000 miles of telephone line across the state. CCC enrollees were on the front lines of fighting wildfires and played a critical role in improving forest health with efforts to control disease and pests harming native stocks of White Pine.

CCC camps in the Palouse helped restore soil and erect soil protection barriers, in and southern Idaho the CCC helped to finish building the canals that play such an integral role in delivering water to crops.

In the late 1930s, the direction of the CCC mission changed toward national defense and preparedness as war in Europe intensified. The CCC in 1939 was moved to the Federal Security Agency, meaning enrollees could receive training applicable to the U.S. entering World War II. While training for combat was prohibited from CCC camps, hundreds of thousands of enrollees had learned the kind of discipline, teamwork and physical conditioning should the U.S. enter the conflict overseas.

When the U.S. finally entered the war on Dec. 8, 1941, many of the new noncommissioned officers turned out to be CCC veterans. The CCC was officially closed in June 1942.

Written by Todd Dvorak

If you stroll through Downtown Historic Weiser, you’ll undoubtedly see a castle façade tucked amidst the usual brick storefronts. Complete with sweeping Tudor arches, glass plate windows, stained glass transoms, cylindrical pilasters, and crenelated battlements, the Romanesque Revival style of this building is a whimsical nod to late 10th- through 12th-century European architecture. Except for areas of natural staining from environmental exposure on the stonework, the building looks much as it did initially. The first-story awnings added in previous decades have been removed, and the central stained glass window, once boarded, is entirely on display.

In 1904, the Boise architectural firm John E. Tourtellotte & Company designed a structure that would become a landmark in Weiser-the Knights of Pythias Lodge Hall. The Weiser Signal hailed it as a “handsome new building” that would be a credit to any city. The Pythian Castle, one of the few buildings designed by Tourtellotte & Company in Weiser, was originally owned and commissioned by the city’s Knights of Pythias. The Weiser Lodge, incorporated on March 27, 1897, has its roots in a fraternal organization dating back to 1864 in Washington, D.C.

During their formative years, Weiser members of the Knights of Pythias convened at the city’s Independent Order of Odd Fellows Hall, and two societies agreed that they would share the building. Saturday night on their inaugural assembly, the Knights of Pythias adjourned at 7 o’clock for supper—and to allow the Odd Fellows their regularly scheduled meeting—and returned to session at 9 o’clock. They concluded their final adjournment around 5:30 Sunday morning, completing all initiations and lodge business. As a modest number of 25, the Knights of Pythias Lodge christened itself Myrtle Lodge No. 26, with Monday evenings declared for regular sessions.

Steady membership growth enabled financial milestones to be reached. In February 1904, the Knights of Pythias announced plans in the Weiser Signal to build a castle hall on a lot they had purchased on East Idaho Street. By August of that year, they had all necessary approvals; in September, they began accepting construction and fine trade bids, eventually securing Tourtellotte & Company as the architect. The grandness of the new Castle Hall reflected members’ aspirations for equal prestige alongside the older secret societies; it also represented ambitions of an emerging business class developing in Weiser and across the United States.

Local newspaper coverage estimated the Pythian Castle over $9,000 or $10,000 in final construction costs. (Comparatively, the city’s Odd Fellows hall cost $7,000 in 1891.) Sandstone for the castle façade was quarried at nearby Sand Hollow and hauled by wagon to town, where it was meticulously cut and custom fit onsite. First-floor occupancy of the two-story building was anticipated by January 1905. At least by February, the Weiser Lodge was holding its regular meetings, as mentioned in the 41st celebratory announcement for the Knights of Pythias order in the Weiser Signal. On Monday, June 12, 1905, Grand Chancellor Charles R. Foss presided over the structure’s formal dedication ceremonies to the order’s principles.

Although no longer used as a lodge hall, the building’s legacy continues. Through the Idaho State Historic Preservation Office, the Pythian Castle was officially listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. In 1982, the building was owned by the Weiser Architectural Preservation Committee. Today, the Pythian Castle celebrates its 120th construction anniversary under the lease of Co-Opportunities Inc., a non-profit business founded in 2017 that teaches the community arts, crafts, music, and basic living skills like cooking. The Castle serves as the main office of their Bee Tree Folk School and museum space for the Simpson-Vassar Collections.

Written by Katie Hall

Next to the jagged peaks of the Sawtooth Mountains and the flowing waters of the Middle Fork of the Boise River sits the sleepy town of Atlanta, Idaho, home to nearly 20 full-time residents. Now known as a haven for outdoor enthusiasts, this town was once an industrious community with hundreds of prospectors, miners, shopkeepers, and others drawn to potential of a Western pioneer town.

In 1863, a prospector named John Stanley was searching for gold around the basin that now bears his name. Scant yields led him further south, where he struck gold along the Yuba River, just a few miles from what we now know as Atlanta, Idaho. Following the news of Stanley’s boon, miners soon flocked to the area, and after a substantial lode discovery in 1864, Atlanta was established as a mining town.

From 1864 through 1867, Atlanta saw an influx of placer miners, immigrants, and merchants. Many of the new settlers arrived because of unrest from the Civil War further East and South, and the name Atlanta was chosen by Confederate miners who incorrectly reported General Hood’s victory over General W.T. Sherman in Georgia. While Atlanta’s population was slowly growing, outside investors became interested in building mills and opening mines, but the town’s remoteness, harsh weather, and rugged terrain kept most development at bay. In 1865, the only road into Atlanta came up from Rocky Bar, the county seat at the time, and winters made it nearly impossible to access, much less transport heavy equipment and materials. In fact, within the first two years of settlement, at least six mailmen died in snowslides while delivering mail to Atlanta and nearby towns.

In 1868, motivated British investors finally began funding the construction of the Lucy Phillips Mill in Atlanta. Following suit, a company from Indiana began construction on the nearby Monarch Mill in 1869, but within a few months into operations, ore recoveries proved less rich than hoped, leading to a lull in operations for a few years.

Despite the hiatus, small mine operators and placer miners stayed persistent, and the Atlanta community saw the additions of a postmaster, butcher, blacksmith, lumber manufacturer, and brewer. In 1870, the town had its first brewery and billiard hall, the Atlanta Brewery, which crafted beer from local hops. Chinese migrants and placer miners also settled in Atlanta and established China Basin, a small camp on the north side of the Boise River. Improvements in ore recovery and a new road into town facilitated further growth, and by the mid-1870s, Atlanta had grown to a population of about 500.

Mills in Atlanta successfully produced gold between 1878 and the early 20th century, but the scarcity of high-grade ore, milling costs, and legal battles between unpaid creditors impeded significant economic development and growth of Atlanta. In 1907, the Atlanta Miners Company constructed the Atlanta Dam and Power Plant on the Boise River to power the mine, mill, and town. Unfortunately, a year later, a fire on Main Street claimed the Atlanta Brewery, The Atlanta Hotel, Greylock Saloon, and the Butler Store.

After years of rebuilding, improvements in the 1930s helped open Atlanta to easier intrastate commerce and more efficient mining practices; The Middle Fork Road expedited travel between Boise and Atlanta, and the introduction of the amalgamation-floatation concentrator in 1932 nearly eliminated the long-standing issue of recovery that plagued mills for decades. From 1932 through the Great Depression and WWII, the Atlanta mining district went on to successfully produce at scale until 1953. According to estimates, from 1864 to 1953, the Atlanta mining district produced approximately $16M – $18M in silver and gold, with the majority coming after 1932.

In 1939, Talache Mines, Inc. acquired the Monarch Mine, Last Chance Mine, and all previously established mining properties along the Atlanta lode. After WWII, production sharply decreased for Talache, and most of the mining effort shifted to smaller, higher grade ore shoots. Talache ceased mining operations by 1953 and leased out parts of the mine to smaller miners who continued producing limited amounts of ore until 1963. At this point, the population, community, and economy had all but left Atlanta and moved on to different parts of the state.

John Stanley and his party tried keeping the location of Atlanta a secret, but the town’s significance to Idaho’s history cannot be understated. Today, Atlanta is a living ghost town with several relics of the booming years. It’s now mostly known as a paradise for backcountry lovers, but visitors can explore shops and travel back in time by touring buildings on the National Register of Historic Places.

Written by Noé Zepeda

Sources:

https://history.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/0365.pdf

https://history.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/0202.pdf

https://history.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/0009.pdf

https://history.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/0494_Atlanta-Dam-and-Power-Plant.pdf

https://www.theatlantaschool.org/archives/2019/2/5/atlantas-pioneer-past

https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/idaho/atlanta/

https://www.goldrushnuggets.com/gosimiinatid.html

U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2004-1205: Preliminary Report on the Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Atlanta Hill Area, Elmore County, Idaho

https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2004/1205/of2004-1205.pdf

History of the Boise National Forest 1905-1976: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1p32WI_ir8raPCUA28zGAbMrZaQYi-12p/view

What do the giant salamander, square dance, and potato all have in common? While this may sound like a setup for a joke, these are all examples of Idaho’s state symbols—the state amphibian, state folk dance, and state vegetable, respectively.

State symbols or emblems are legally approved representations of a state’s character, history, goals, and landscape. Each state has its own collection of symbols, some of which include state soil, state sport, and state cat. Since Idaho entered the union, the state’s symbols have been unique, quirky, and, frankly, Idahoish because they represent a state that takes pride in its distinct environment, people, creatures, and culture. In fact, Idaho’s first symbol was its state seal, which was chosen in 1891 through competition. A Boise art instructor named Emma Edwards Green submitted an entry that depicted the resources and industries of Idaho at the time. Her design won unanimously and was declared the official state seal by Governor Norman B. Willey. Although it received a touchup in the 20th century, Idaho’s seal remains the first and only state seal designed by a woman. Nearly 20 years following the adoption of the state seal, Idaho approved its flag in 1907, which is still in service today and depicts the seal in the center of a blue rectangle.

After establishing its two primary icons, state legislators welcomed efforts to grow the list of Idaho’s trademarks. In the 1930s, the legislature approved adding the state bird (Mountain Bluebird), state flower (Syringa), and state tree (Western White Pine). “Here We Have Idaho,” the song composed by Sallie Hume Douglas in 1915, became Idaho’s State Song in 1931. It might not have as much airplay as Sweet Home Alabama or New York State of Mind, however, it’s still popular in Idaho’s elementary schools and around Moscow as the University of Idaho’s alma mater.

Following the mid-century, Idaho dug further for some of its subsequent symbols, such as the state gem (Star Garnet) and state fossil (Hagerman Horse). The Hagerman Horse is a relic of the horses that once roamed North America more than 3 million years ago and is the oldest known relative of the modern horse. In 1928, a farmer in Gooding County uncovered the first set of Hagerman Horse bones at a site that eventually became the Hagerman Fossil Bed. To date, the fossil bed has yielded the remains of more than 200 horses and 200 other species of pre-historic animals. In 1988, the Hagerman Fossil Bed became a national monument, and the Hagerman Horse became the state fossil that same year.

Idahoans’ appreciation for wildlife is evident through an assortment of iconography. The Hagerman Horse is the second horse symbol recognized by the state, with the first designation going to the Appaloosa as the state horse. Other animal symbols include the state fish (Cutthroat Trout), state insect (Monarch Butterfly), state raptor (Peregrine Falcon), and even state dinosaur (Oryctodromeus). The Oryctodromeus, or Orycto for short, was a small burrowing dinosaur found only in eastern Idaho and the southwest corner of Montana. In 2022, a group of elementary school students in East Idaho persuaded legislators to introduce the Orycto as the state dinosaur, and in 2023, the bill passed both chambers with little resistance.

Idaho’s selection of state symbols can also generate vigorous debate, however. In 1997, students at Boise’s Summerwind Elementary School noticed no state reptile. They petitioned on behalf of the rattlesnake, a species they said embodied the courage and bravery of Idaho citizens. Legislators brought it to a vote, but the proposal was shot down because of the rattlesnake’s nuisance to those working in Idaho’s agriculture industry. Another symbol that went to vote but was rejected by the Senate was the Silver Tipped Sagebrush as the state bush in 1988. Surprisingly, the potato was introduced as a state symbol in the early aughts, and even then, it was debated whether it would be appropriately classified as a vegetable. A group of 4th graders made the case to lawmakers in 2002 and after putting it up to vote, the spud became the state vegetable.

Currently, Idaho has close to 20 State Symbols, ranging from state fruit to state motto. As the state continues to trace its history and shape its identity, one can only anticipate that more state symbols will emerge thanks to the enthusiastic and visionary 4th graders residing in all corners of the state.

Written by Noé Zepeda

Decades before the Boise State University Broncos took to the Blue Turf and pedestrians crossed Friendship Bridge on the Greenbelt, the BSU campus was actually the site of one of the country’s first commercial airmail trips, the country’s longest airport runway, and the birthplace of an airline that would later become United Airlines.

It all began in 1926 when WWI pilot Walter T. Varney successfully bid for 40 acres of city-owned marshland and built the first municipal airport to fly commercial mail throughout the Western United States via Varney Airlines. Constructed mostly on a gravel bed, the original airport spanned the Boise River between Capitol and Broadway Avenue. It served as a hub for Varney Airlines to deliver mail to places like Pasco, WA, Elko, NV, and other towns. Within a few years of the maiden flight, Varney Airlines introduced passenger travel in 1930, carrying travelers four at a time. That same year, United Aircraft and Transportation Company purchased Varney Airlines, a merger that would ultimately become United Airlines.

As demand for air cargo and air travel grew, so did the Boise airport. By 1938, the airport’s runway had expanded from its original 2,000 feet to 8,800 feet –the longest in the country. At the same time, Boise Junior College (now Boise State University) was expanding, and its Board of Trustees applied to move the college to the airport to ease accessibility for in-and-out-of-state students. Between sharing space with the college and larger airplanes necessitating more extensive facilities, the airport relocated its operations to a plot of land in the southern part of the city where the current Boise Airport resides. After the move, Boise Junior College bought and used the old hangars and airport to teach ground and flight school, offering a semi-professional degree until 1946. The college kept the airstrip until the 1950s and eventually built over it to create additional space for Bronco Stadium, resulting in the current campus’ relatively linear layout.

Operating out of its new and current location, the Boise Airport started as a joint-use airport serving air mail and cargo, passenger, and military services. With WWII looming, the U.S. War Department posted military personnel at the airport in the early 1940s and named it Gowen Field in honor of 1st Lt. Paul R. Gowen of Caldwell, who was killed when his twin-engine Army Air Corps bomber crashed in Panama. During WWII, the Army Air Corps leased Gowen Field as a training base and stationed over 6,000 men (including actor Jimmy Stewart). After the war ended, the War Department turned over the airport to the City of Boise in 1946, when the Boise Department of Aviation and Public Transportation began managing it.

Air travel became far more popular and accessible in the 1950s and 60s, with the number of enplaned passengers in Boise reaching 86,000 in 1961 and nearly doubling to 148,000 by 1966. United Airlines was the first company to offer jet service to and from Boise in 1964, and by 1969, the Boise airport had its first concourse. The airport added its second concourse in 1979 and used its outgrown hangar as part of the terminal until renovations in 2003.

Nearly a century since its first flight, the Boise Airport has come a long way and shows no signs of slowing down. The Treasure Valley’s boom as both a living and tourist destination has facilitated further development at the Boise airport, including two parking structures, a new rental car facility, and a new concourse by 2025. BOI is on course to surpass 4,000,000 total passengers, 100,000,000 freight items, and 7,000 military operations for the 2024 calendar year.

Written by Noé Zepeda

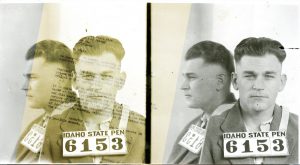

William “Teton” Jackson (#111) operated a gang of a dozen men out of Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and stole horses from the surrounding territories. He earned the nicknames “The Prince of Horse Thieves” and the “Scourge of the Four Frontiers.” Wanted in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, and Nevada for horse theft, Sheriff Frank Canton finally apprehended him in 1885. The court sentenced Teton to 14 years of hard labor in the Idaho Territorial Prison for Grand Larceny.

On August 28 of the following year, Teton, accompanied by Scott Holbrook (#112), escaped from the penitentiary after digging an 11-foot tunnel under their cell with a spoon after months of discarding excess dirt each morning while emptying their bathroom bucket. Captured in Montana with stolen horses, Teton returned to the Idaho prison in 1888.

On April 6, 1892, Teton received a pardon after serving just under five and half years in the Idaho Penitentiary, due in part to a petition for his release and testimonials from the guards of Teton’s “moral as well as physical courage.”

The most remarkable part of Teton’s life is what happened to him after prison. Teton, one of the most wanted outlaws of the Rocky Mountains, gave up his life of crime. He settled in Wyoming and married Mary Calhoun, a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Nation. Together they had four children.

Teton spent the rest of his life working as a guide to different hunting outfits in the mountains. In his free time, he played the violin and avidly collected magazines and books. He passed away in 1927 at age 72.

Explore Teton’s entire story and how it intersects with Sheriff Frank Canton in episode 88 of the Behind Gray Walls podcast.

Written by Samuel Anderson

In 1947, countries were still reeling from the toll WWII was having on life, infrastructure, and the economy. Stateside, Americans were helping returning veterans adjust to post-war life and getting businesses back on their feet. But many were also conscious of the long road to recovery for our allies overseas. Coinciding with conversations and policies to help Western Europe rebuild, a grassroots movement called the American Friendship Train brought Americans together to collect and donate food, medicine, equipment, and clothing that would be shipped to Europe and distributed by rail.

Although the American Friendship Train traveled throughout Western Europe, the French were the biggest recipients of the provisions. No strangers to love languages, France responded by crowdsourcing its own gift for the Americans and sent over the Train De La Reconnaissance Françoise Au Peuple Americains, otherwise known as the French Gratitude Train or Merci Train. Through this initiative, the French packed 49 boxcars with public donations and shipped them across the Atlantic, designating one for each state and one for both Washington D.C. and the Territory of Hawaii. Boxcars were overflowing with items of French culture, history, and character and none had the same contents.

The Merci boxcar destined for Idaho arrived in downtown Boise on February 22, 1949, bearing its unique coat of arms to a crowded reception with a parade, speeches, and media coverage. Veterans, politicians, and Francophiles were on hand to celebrate and admire the gifts from the French. Among the items displayed that drew the most attention was a sculpted replica of the Winged Victory of Samothrace, now a distinguished fixture of the rotunda inside the Idaho State Capitol building.

In the years following its ceremonial arrival, Idaho’s Merci Train boxcar was relocated around Boise several times, but unfortunately was neglected and fell into disrepair. In 1977, members of the American Legion and the Idaho State Historical Society coordinated an effort to preserve the boxcar and move it to the Old Idaho Penitentiary. By 1980, it finally arrived inside the prison walls where it remains today. With the help of military veteran and history enthusiast Tom Brown, the Merci Train boxcar was restored to its original shape and color with a new coat of Ponderosa Blue 51. The contents that once packed the boxcar were donated to the Idaho State Historical Society and sorted for exhibit, including old artillery shells, dishware, and even a wooden stool handcrafted by a blind octogenarian. Despite all boxcars having distinct gifts, each included one “Friendship Cord” made of red, white, and blue threads from the French and American flags that flew atop the Eiffel Tower on Liberation Day in 1944. Incidentally, Idaho received two Friendship Cords.

Idaho’s Merci Train is still located at the Old Idaho Penitentiary and serves as a reminder of a shared goodwill between the United States and France. And although trains may not always translate to thanks, it is fitting that gratitude is the same in both English and French.

Visitors to the Old Pen can view the Merci Train during business hours by appointment. For more information, visit history.idaho.gov/oldpen.

Written by Noé Zepeda

Lewiston, Idaho, nestled along the banks of the Snake River, has a rich history intertwined with the development of north Idaho’s steamboat transportation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although the region’s large lakes—Coeur d’Alene and Pend Oreille—boast of a flurry of steamboats that ferried miners, supplies, and later excursionists across the majestic waters, Lewiston’s water transportation history is equally important to the state’s economic development. The arrival of steamboats to Lewiston, provoked by the gold rush along the Clearwater River watershed, had a profound impact on the region’s growth, economic prosperity, and transformation into a bustling hub of commerce.

Before 1855, there needed to be more water transportation on the upper Columbia River watershed. Tributaries of this system include Idaho’s Snake River and Clearwater River. In the early 1860s, pioneers and gold seekers were only beginning to understand the water infrastructure of these two Idaho rivers. Yet, by 1863, Idaho’s first territorial governor would select the burgeoning town of Lewiston at the confluence of these rivers as the territory’s first capital city. In the early 1860s, a water navigation company, The Oregon Steam Navigation Co., controlled most of the steamboat traffic in the region. The first recorded steamboat to reach Lewiston was the SS Colonel Wright in 1861, under the command of Captain Thomas Stump. Before this, Lewiston had been a remote and isolated settlement accessible only by arduous overland journeys. The arrival of steamboats opened the region to trade, connecting it to the broader network of river transportation, even if this transportation was only feasible during high water and spring runoff. If not for Stump’s daring 8-day journey up the Snake River over rocks and through rapids, this revolutionary breakthrough in transportation may have been left untapped. This accessibility by steamship, in turn, attracted settlers and businesses to Lewiston, boosting its population and economic activity.

Steamboats remained crucial for transporting essential commodities like timber, which was readily available in North Idaho’s forests, and wheat once irrigated agriculture reached the region. They facilitated the export of resources from the inland region to the coast and enabled the import of essential goods for the town’s growth. This exchange had a profound impact on Lewiston’s development, as it established the town as a vital link in the regional supply chain.

The heyday of steamboats in Lewiston was during the late 19th century and the early 20th century. However, with the advent of improved railroads and roads, steamboat transportation gradually declined. By 1893, the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company had laid tracks along the south side of the river. As a result, steamboat transportation virtually ended on the Columbia and Snake Rivers above the Dalles, at least until November 1896, when the Cascade Locks and Canal were completed, allowing open river navigation from Portland to The Dalles.

The history of steamboats in Lewiston, Idaho, is a captivating tale of transformation and progress. The arrival of these majestic vessels not only connected the town to the rest of the region but also catalyzed its growth and economic development. While the era of steamboats has passed, the legacy of this remarkable period is still evident in the town’s historical sites and the collective memory of its inhabitants. Additional development of locks and dams along the Columbia River has made the river’s navigation possible, meaning that today, Lewiston is the most inland seaport on the West Coast. Located 465 river miles from the Pacific Ocean, Lewiston can still receive cargo barges and other boats, keeping it connected strategically to the Pacific Northwest’s water transportation systems and making the chapter of steamboat history in Lewiston a vital reminder of the indomitable spirit of pioneers, and the legacy of their work in laying a foundation for today’s economic opportunities.

Written by Mark Breske

Following prospector Elias Davidson Pierce’s gold discovery in the Boise Basin in 1860, many vaqueros (cowboys) in Idaho transitioned to mining and mule packing. Many more Mexican laborers arrived in the Gem State, bringing essential skills that helped develop Idaho’s mining industry. As miners, Latinos developed mining districts, and as mule packers, they became the lifeline of remote mining towns by providing them with merchandise and goods. They left place names such as Orofino, Alturas, and Esmeralda.

This influx took shape in cultural hubs throughout the state. One of the most influential examples first emerged at 115 Main Street in Boise. In the 1860s, vaquero and local herder Antonio de Ocampo rented part of Boise’s Block 29 on Main, where Mexican laborers stayed in Boise. He welcomed muleteers like Jesus Urquides and Manuel Fontes. De Ocampo later bought this parcel of land known as Spanish Village. The village served as an ethnic center for the Spanish-speaking population, and after De Ocampo died in 1878, his good friend Jesus Urquides inherited the land.

Jesus Urquides, born in Sonora, Mexico, belonged to a remarkable generation of Mexican mule packers throughout the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. He started a pack-train operation in California in 1850 at seventeen. In 1877, the government contracted Urquides to supply federal troops during the Nez Perce War.

Urquides utilized his business acumen in Idaho. He transferred his operation to Boise and began supplying local miners with food and supplies. Urquides built stables and corrals to accommodate his outfit and established a freight business on his inherited land. Boise’s Spanish Village became a hub of Hispanic culture.

Jesus Urquides’s contributions to what was little more than a ‘frontier boomtown’ helped establish Boise as a flourishing community within Idaho. He died in 1928, and his daughter Dolores “Lola” Urquides Binnard continued renting out the cabins and giving tours for tourists, keeping her father’s legacy alive. By 1956, Spanish Village had roughly 20 tenants, and after Dolores passed away in 1965, the buildings fell into disrepair and became a sore spot. The city condemned and tore the cabins down in the early 1970s.

During its sesquicentennial, the City of Boise established a memorial where the Spanish Village once stood to honor Urquides’ legacy.

Written by Mark Breske

Outside of movie theaters and disco clubs, one of the largest attractions in the 1970s was the stunt work of Robert Craig Knievel, otherwise known as Evel Knievel. Famous for death-defying jumps with his motorcycle, Evel knew how to draw crowds throughout the ’60s and ’70s, and forty-nine years ago, he brought national attention to Southern Idaho when he attempted to jump the Snake River with his X-2 Skycycle on September 8, 1974.

Knievel developed a taste for doing tricks and stunts around his hometown of Butte, Montana, from an early age, usually in front of friends, schoolmates, and even coworkers. Although most people enjoyed his acts, sometimes they landed him in trouble. After crashing his motorcycle and being arrested for reckless driving in 1956, Knievel heard one of the other inmates, William Knofel, referred to as Awful Knofel. Knievel liked the rhyme scheme and adopted the name “Evel” Knievel, swapping out letters because he didn’t want to be considered evil.

His early jumps as the Evel Knievel act had him jumping over boxes of rattlesnakes, pools, cars, and pickup trucks. As he gained attention, he started performing more impressive jumps to outdo himself, clearing 50 stacked cars or the Caesar’s Palace fountains in Las Vegas. Evel successfully positioned himself in the national spotlight after appearing on talk shows, ABC’s Wide World of Sports, and record books, so riding the momentum, he set his eyes on his next big jump over the Snake River in Twin Falls, just west of Shoshone Falls.

On the day of the Snake River Jump, Evel was dressed in his white, American-themed suit and facing a large crowd of onlookers eager to witness history. For this jump, Evel hired aeronautical and NASA engineers to build a rocket-powered cycle with enough force to launch him up and over the gorge, using a parachute to safely reach the ground on the other side. Just after take-off, his parachute deployed and slowed down Evel so much that he only made it about halfway across the quarter-mile-wide gorge, sailing down towards the river on the same side he launched from. Evel survived with a few minor injuries, but had he landed a few feet further into the water, he would have drowned because of a harness malfunction. Despite the outcome, the crowd cheered on and fans praised him for his bravery and ingenuity.

Evel continued riding and performing around the country until 1980 when he retired and shifted his focus towards supporting his son Robbie’s daredevil career. In 2007, at the age of 69, Evel passed away after a long bout with diabetes and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and he was laid to rest in his hometown of Butte. Evel’s career and persona left a lasting impression on people across the globe; forty years after Evel’s Skycycle took off from the south side of Snake River, stuntman Eddie Braun successfully jumped the gorge with his rocket-powered motorcycle named “Evel Spirit” on September 16, 2016. Now, when visitors walk Twin Falls’ Centennial Trail, they can see the ramp where Knievel took off, as well as a monument to Evel’s jump in 1974 at the city’s visitor center.

Written by Noé Zepeda

The history of the Boise School District is a testament to the growth and development of education in the capital city of Idaho. The district’s evolution mirrors the societal changes and educational advancements that have shaped the region and the nation.

The origins of the Boise School District can be traced back to the mid-1860s when the city of Boise was experiencing rapid growth due to the discovery of gold and the expansion of the railroad. As the population increased, so did the demand for education. In 1864, the Territorial Legislature established a public school system in Idaho Territory. Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon appointed J.B. Knight as the Ada County superintendent in 1865, where he established School District No. 1, and the first public school, marking the beginning of formal education in the area.

In the early years, common schools were small and often located in makeshift buildings. However, as the city flourished, there was a growing recognition of the need for more organized and comprehensive educational facilities with sustainable financial support. This demand led to the first tax levy in September of 1868 to fund public education with tax revenue. Dedicated school buildings like the iconic Boise High School were integrated into the city’s planning and design and are still operational today.

Boise embraced three school districts in 1880 to manage higher enrollment rates and the financial strain of the school system. Territorial Governor John Baldwin Neil signed a bill on February 4, 1881, officially creating the Independent School District of Boise City No. 1. Of all the provisions afforded in the bill, granting a Board of Trustees power and authority to propose a budget, conduct public hearings, and determine tax revenue supporting the budget, has proven to be among the most important.

A newspaper article from the Idaho Triweekly Statesman from October 6, 1885, indicated that Central School was divided into four departments: 1) primary, 2) intermediate, 3) grammar, and 4) high school. Music and art were said to be taught in the first three departments in addition to the traditional courses of reading, writing (including penmanship), arithmetic, and social studies. Garfield High School students studied higher math, science, and college prep courses in the classics. In 1888, bookkeeping was added to the high school curriculum. The Boise District had one of only two high school programs before statehood in 1890. The first graduating class 1884 included two students: Tom G. Hailey and Henry Johnson. The class of 1885 doubled and included women: Hetty Cahalan, Mary Cahalan, Harry Humphrey, and Philo Turner. The sizes of the graduating classes continued to increase. In 1887 there were eleven graduates; by 1900, there were twenty-three, and by 1910 the number had increased to seventy-two. By 1920 there were 151 graduates, and within ten years, the number of graduates had reached 223 (boiseschools.org).

While the school district’s enrollment increased greatly from 1881-1930, Boise City’s physical limits also increased as the city annexed surrounded townships and county property. With these annexations, smaller rural schools that developed around the City of Boise out of necessity before 1881 found themselves within city limits, and many opted to join the more extensive Boise District. Hawthorne was the first district to annex in 1907, followed by Garfield in 1910, Lowell in 1909, Collister in 1922, and Whitney in 1923.

In recent decades, the Boise School District has strongly emphasized academic excellence, preparing students for higher education and the workforce. Rigorous academic standards, advanced placement programs, and a wide range of extracurricular activities have become integral parts of the district’s offerings. Additionally, as technology became more prominent in education, the Boise School District adapted to the digital age. Today, computers and the internet have transformed how students learn, and teachers instruct. The district embraced these technological changes, incorporating digital resources and tools into its classrooms to enhance the learning experience. Community involvement has also been a hallmark of the district’s history. Parents, educators, and local leaders have collaborated to ensure the best educational experience for Boise’s students. Bond measures and community support have enabled the construction of state-of-the-art facilities and the implementation of innovative educational initiatives.

The history of the Boise School District reflects the region’s growth, evolution, and adaptability of education. From humble beginnings in the late 1800s to today’s modern, technology-driven classrooms, the district has continually transformed to meet the changing needs of its students and the community. As Boise’s population grows and society evolves, the district’s history serves as a reminder of education’s crucial role in shaping the future.

Written by Mark Breske

Source: https://www.boiseschools.org/our_district/district_history

The history of the telegraph in Idaho is intertwined with the development of the American West and the expansion of communication networks across the region. During the 19th century, the telegraph played a vital role in connecting remote areas and facilitating communication in Idaho. The Western Union Telegraph Company connected the first transcontinental telegraph system from the eastern United States to San Francisco in 1861. It was an immediate success that swiftly replaced the Pony Express as the preferred means of long-distance communication. The first telegraph lines reached Franklin, Idaho, in 1866 as part of the continued broader effort to establish telegraphic connections across the United States. Lewiston became the first town in northern Idaho linked to the telegraph in 1874 and was later the first town in the Pacific Northwest to host a telephone call made by businessman John P. Vollmer in 1878.

The establishment of telegraph lines in Idaho had significant implications for various aspects of society. It facilitated the development of trade and commerce by providing a means of transmitting business orders, market information, and financial transactions. The telegraph allowed merchants and miners in Idaho to stay connected with markets and business centers elsewhere. Furthermore, the telegraph played a crucial role in disseminating news and information. It enabled newspapers in Idaho to receive updates, national news, and other important information rapidly. This ensured that the residents of Idaho were kept informed about current events and developments occurring beyond their immediate surroundings.

The telegraph also impacted transportation and travel in Idaho. It allowed for the coordination of train schedules, improving the efficiency and safety of railroad operations. Telegraph lines were often installed alongside railway tracks, providing instant communication between stations, and enabling the smooth functioning of the growing railroad network in Idaho.

Over time, the telegraph network expanded throughout Idaho, reaching more towns and communities. Telegraph offices and stations became integral parts of the social and economic fabric of the region. They served as activity hubs, where skilled operators sent, received, and decoded messages. However, as technology advanced, the telegraph’s dominance began to wane. The telephone emerged as a more direct and interactive form of communication, gradually replacing the telegraph for personal and business conversations. By the early 20th century, following the end of World War II, the telegraph had been mainly superseded by newer technologies.

Nevertheless, the telegraph left a lasting legacy in Idaho. It played a crucial role in connecting the state with the rest of the country, facilitating communication, trade, and transportation. The telegraph network laid the foundation for subsequent advancements in communication technology, eventually leading to the development of modern telecommunications systems.

Today, the telegraph’s influence can be seen in the historical sites and artifacts related to its operation in Idaho. Museums, exhibits, and preserved telegraph stations provide glimpses into this transformative era of communication and its impact on the state’s development.

Written by Mark Breske

Conversations about an untapped natural resource in Boise began around Idaho’s transition into statehood. Geothermal energy became realized in a swampy area known as Kelly Hot Springs near the Old Idaho Penitentiary in late 1890. Warm water was found on December 24, and one month later, drillers struck a large flow of hot water. By the spring of the same year, 800,000 gallons of pure water flowed from the well each day. Soon after, plans were made for a resort to commercialize the new abundant resource. On May 25, 1892, Boise’s first large-scale natatorium opened.

C.W. Moore founded the Boise Artesian Hot & Cold Water Company to further develop the resource after successfully using hot water to heat his home. He recruited architect John C. Paulson to design the heated bathing resort. Once the Boise Natatorium opened, it quickly became a popular recreational destination. The impressive and efficient design was inspired by the Moorish Revival style, complete with a 125-foot-long swimming pool filled with natural hot water. The interior also featured a lava rock diving platform, wooden truss arches, and a mezzanine around the pool. Aside from swimming, guests could also enjoy a dining area, gym, baths, dance floors, card and tea rooms, and a saloon.

The combination of wood and moisture caused the structure to rot. In 1934, a windstorm forced a beam to fall, prompting the end of the Boise Natatorium as so many people had come to know it. Boise City reopened the pool shortly after as an outdoor swimming area, which continues to operate today.

Geothermal heat became much more than a novelty, and homes on Warm Springs began incorporating the energy source into their construction, plumbing in with wooden pipes initially. The wooden pipes were exchanged for metal in 1896 after being deemed “dangerous and useless,” which allowed the system to grow. The plumbing upgrade increased the natural flow from 800,000 gallons to 1.2 million daily, providing more access to residential and commercial dwellings. Nine miles of pipe funneled geothermal water to all customers for 2-3 dollars per month—a rate that remained reasonable at the height of geothermal popularity. As late as 1958, 244 customers continued to use natural hot water for domestic use and heat.

Many buildings in the downtown Boise area continue to utilize geothermal energy as a heat source today, with over 20 miles of pipeline to more than 6 million square feet of building space. If you walk around downtown, you can see the plaques indicating that a building uses geothermal heat as an energy source. Local artist Ward Hooper designed the plaques. Geothermal energy is found throughout the Gem State, and we are one of just seven states with utility scale electricity generation from geothermal energy. With its vast volcanic landscape, Idaho has over 1,000 wells and 200 natural springs. Idaho is the only state in the nation with a capitol building heated by geothermal energy.

Written by Mark Breske

The Sacred Heart Mission, also known as Cataldo Mission, is located in northern Idaho and is the oldest building in the state. The mission was the second Jesuit mission in the area. The first was St. Mary’s, established among the Flatheads in Montana in 1841 by Father Pierre-Jean De Smet. Father De Smet was instrumental in establishing several missions throughout the Pacific Northwest, including the St. Ignatius Mission in Montana and the Sacred Heart Mission in Washington.

While traveling for supplies in 1842, De Smet met Coeur d’Alene chief, Twisted Earth, whose father, Chief Circling Raven, had in 1740 prophesied the coming of the “Black Robes” (Jesuit missionaries) with special powers who would provide spiritual help for the Coeur d’Alene people. In response to a request from the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, De Smet sent Father Nicholas Point and Brother Charles Huet to establish the mission along the St. Joe River near the southern end of Lake Coeur d’Alene. Due to ongoing flooding in the area, Point moved the building site from its original proposed location near the St. Joe River to a hill overlooking the Coeur d’Alene River 27 miles east of the lake, where it still stands today.

Construction materials were limited, including no nails being used. The Coeur d’Alene people quarried fieldstones for the foundation and mixed clay and water to create a bonding mortar. They shaped nearby trees into sills, posts, and beams, using pulleys with hemp rope to secure them into place. They weaved grasses and saplings together and applied a coat of clay, creating a “wattle and daub” insulation. The design of the mission was inspired by Father Antonio Ravalli, a priest stationed at St. Mary’s in Montana who had learned construction skills like woodworking and bricklaying in Italy. The Sacred Heart Mission was constructed by Jesuit missionaries and members of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe between 1850 and 1853.

In 1873, President Grant issued an Executive Order creating a reservation for the Coeur d’Alene people that excluded the mission, which forced the Tribe to move out of the area. Father Joseph Cataldo, who had begun ministering to the Coeur d’Alenes in 1865, made the recently vacated mission his headquarters when he became Superior-General of the Rocky Mountain Missions in 1877. Cataldo continued to use the facility for a decade. Over time, the church was being used less, aside from being a transportation hub connecting steamboats from Coeur d’Alene with trains to Wallace and other mining towns in the 1880s. The mission was no longer being maintained and subsequently began to fall apart. Though the building was repaired in 1884 by Father Joseph Joset and again in 1910 by Father Paul Arthuis, the Jesuits realized they could not afford the upkeep of the structure. In 1924 they deeded the mission and its property to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Boise led by Bishop Gorman. In 1925 Bishop Gorman initiated a funding campaign to restore the mission. With $12,000 raised, Boise architect Frederick Hummel and contractor James Lowery completed the restoration in 1929.

The Sacred Heart Mission was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1961 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. In 1975, the Diocese of Boise leased the Old Sacred Heart Mission to the Idaho Board of Parks and Recreation, establishing Old Mission State Park and ensuring the landmark’s preservation. In 2001 the Diocese deeded the mission and its property to the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. Ownership of the mission was a meaningful achievement for the Tribe, whose ancestors built and worshipped at the mission. As a testament to the importance of the mission to the Coeur d’Alene people, in 2011, the Tribe built a new $3.26 million visitor center to accommodate a permanent exhibit about the relationship between Jesuits and the Coeur d’Alene people and neighboring tribes. The mission is still a popular tourist destination today. Visitors can tour the mission and learn about the history of the region and the role that the mission played in it. The Sacred Heart Mission is a testament to the dedication and perseverance of the early Jesuit missionaries and a reminder of religion’s important role in the settlement of the American West.

Written by Mark Breske

Source: https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/ID-01-055-0008

The history of beer brewing in Idaho coincided with the search for gold in 1862. At this time, the territory had an influx of German immigrants, bringing along their brewing traditions and changing the history of brewing in Idaho. Before this, American brewers often followed British brewing traditions, their bars serving primarily dark pints of porter and stout. Mining camp brewers were different. Most were immigrants from German-speaking countries with a love for lager, a beer, light in color and body.

In 1862, the territory’s first brewery opened in Lewiston, Idaho. Fueled by gold and the unquenchable thirst of camp miners, many other cities followed suit and thus the brewing boom of Idaho began. By 1880, Idaho had 33 active breweries.

Men like John Lemp, a German immigrant also known as the “Beer Baron of Boise,” started to create change in the brewing industry by creating more large-scale production and sale of beer that highlighted the use of “Idaho Local” ingredients. Such as today’s movement of “Buy Local”, Lemp declared his beer “honest beer” made with “Idaho hops and barley”, fervently reminding Idahoans, “the money you spend helps to employ Idaho labor.” By 1882, Idaho’s breweries set a record for the territory by producing a total of 2,747 barrels of beer.

With the formation of the Anti-Saloon League in the late 1800s, the movement towards Prohibition in Idaho began. This organization dedicated their efforts to the promotion of temperance, or the abstention from alcohol, becoming instrumental in the passage of the early adoption of the Idaho Prohibition Law in 1916. With the start of The Great Depression in the 1930s, a decline in support for Prohibition began. In 1933, the 21st Amendment to the Constitution passed, repealing Prohibition nationwide. Idaho was one of the first states to ratify the amendment, making the production, sale, and transportation of alcohol once again legal in the state.

Unfortunately for Idaho’s breweries, many of them did not make a comeback. Few made it to the 1950s, but all had closed by the 1960s. Due to the national craft beer movement in the 1980s, Idaho started to see new breweries emerge, such as Grand Teton Brewing Company, opening in 1988, and Highland Hollows, opening in 1992.

Today, Idaho is a prominent player in the craft brewing industry. The state possesses more than 80 breweries and produces more than 100,000 barrels of beer per year, according to the National Brewers Association.

Written by Alexandra Polidori

By law, we recognize March 4th each year as the anniversary of the day on which President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 signed the Bill creating Idaho Territory. From the outset, Idaho was formed in the crucible of American history. Two months earlier, the Sixteenth President issued his and our Emancipation Proclamation. Seven months later, Lincoln at Gettysburg would remind us that all men (and women) are created equal.

Just a week after March 4th in the same room at the White House where he earlier pondered and produced emancipation, Honest Abe, gave Idaho an honest start by appointing the first of a total of fifteen loyal “Union Men” which he would send to Idaho to be our earliest territorial officers over the next two years. During the rest of his presidency, Lincoln kept abreast of Idaho political affairs. For instance, he commented in his 1863 and 1864 Messages to Congress on the state of the Territory’s political organization, the wealth of our mineral riches, and the situation of our Native American relations.

But what is not so well known about Lincoln and Idaho is that, at the four greatest speeches ever delivered by him, people with Idaho connections were present and even assisted Lincoln at those most significant and memorable addresses ever delivered on American soil! In February of 1860, not-yet candidate Abraham Lincoln spoke to 1500 people in the basement auditorium of Cooper Union in New York City. At first, the speech was a failure, until he received a prearranged signal from his Illinois lawyer-friend, Mason Brayman from the back of the room, urging him to speak louder and project more enthusiasm. Lincoln did, suddenly engaging the crowd, rousing their passions against the extension of slavery with phrases like

“RIGHT MAKES MIGHT.” Thereby, he instantly became a leading presidential possibility. Brayman, the man who raised his hat on the top of his cane to signal, was appointed Governor of Idaho Territory by President U.S. Grant in 1875 and moved to Boise.

One year later, sorrowful, pensive Abe Lincoln said “Farewell” to a few hundred Springfield, Illinois neighbors in February of 1861 as President-elect, beginning his journey to Washington by train. “I HOPE IN YOUR PRAYERS YOU WILL COMMEND ME”, he told them. In the crowd, were two young boys named Dubois, neighbors who lived across the street and often played with the Lincoln children and even romped and wrested with their father. In 1880, Jesse and Fred moved to Blackfoot. Jesse became the medical doctor for the Shoshone Bannock Tribe. Fred Dubois, in short order became the appointed U.S. Marshall and then was elected Territorial Delegate to Congress for the Territory. In that role, the little boy who grew up on Eighth Street with Lincoln led the successful political campaign to tum Idaho Territory into Idaho state in 1889-1890 and became our first United States Senator.

Written by David Leroy, President, Idaho Lincoln Institute and former Attorney General and Lt. Governor

Idaho had an early interest in boxing. Historical records show evidence of boxing fights in mining camps dating back to the 1890s. The Lewiston Daily Teller published “Boxing for Boys” in 1891. The article stated:

“If a lad is quick to lose his temper, boxing will cure him; it will teach him that no one who lets his temper get the best of him will become an expert sparrer.”

However, not everyone agreed with that sentiment. The Blackfoot News, less impressed with the sport, wrote in 1890:

“The undertaker’s favorite exercise is boxing.”

Idaho eventually caught the boxing fever. Since then, it has remained one of the more active states for boxing in the northwest. Boxing in Idaho, for most of its history, remained a winter sport. Most fights took place in winter and spring due to how many boxers also worked on farms and were needed during the summer and fall.

In 1891, the Idaho Penitentiary held a series of matches between three inmates. Wesley Dunlap, William McCreary “Billy the Kid,” and John Braithwaite. The event sparked a scandal in Boise. Community members demanded an investigation into reports that guards drank and gambled while the inmates boxed. The uproar caused by these boxing matches eventually contributed to Warden Arney’s dismissal and a ban on boxing in the prison.

By 1927 Warden Wheeler lifted the ban, and boxing returned to the site. Between 1936-1940 the prison began holding public fights; non-inmate audience members had to pay 85 cents to watch.

By the end of the sixties, boxing returned to its final and most serious stage here at the prison. Boxers traded the days of unorganized brawls for more serious training regimens. The men, naming themselves The East Side Boxers, began having outside coaches and trainers prepare them for sanctioned amateur fights. Some of these competitors even went on to win local titles and Golden Gloves championships. One boxer even qualified as an alternative for the Olympics during their time in prison. After inmates were transferred to the new facility at the end of 1973, boxing continued for many years at the new facility before the program’s conclusion in the 2000s. During the Old Idaho State Penitentiary operation, 170 plus inmates competed in boxing while serving time.

Written by Samuel Anderson

In 1963, the Bureau of Reclamation proposed construction of the Teton D on the Snake River near in the eastern Snake River Plain to control spring runoff and provide more water for irrigation, hydropower, and drinking. The final dam would be 305 feet tall and have a crest length of 3,100 feet. In 1971, an environmental impact statement was issued for the worksite. The study’s lack of funding, coupled with a lack of site preparation, stalled construction.

Environmental groups moved to stop construction, citing the impacts on fish and wildlife, and degradation of the aesthetic value within the region. While the initial (brief) environmental impact study did not raise questions about a potential collapse, conservation groups questioned the area’s potential for earthquakes. Nevertheless, construction on the Teton Dam, reservoir, and hydro plant began in 1972, and by November of 1975, construction was nearly complete, and filling the reservoir began.

On June 3 and 4, 1976, workers discovered three small leaks below the dam. At 7:30 am on June 5, a muddy seepage appeared. While small dam leaks are not uncommon, these leaks would foreshadow the dam’s impending demise. Shortly after the outflows began, the dam’s embankment began to wash out, and crews moved in with heavy equipment to patch the leak to no avail. Knowing the collapse was inevitable, local law enforcement evacuated residents downstream. At 11:55 am, the dam’s crest caved, compromising the structure. Over 2 million cubic feet of water per second spilled into the area below, quickly and devastatingly running through thousands of homes and businesses, leaving 11 people dead and a wake of destruction totaling more than $400 million in damages. The effects of the disaster also had long-term impacts on the fish and wildlife populations. Rebuilding the surrounding communities and cleaning up the debris took several years.

An investigation by geologists concluded that the area’s propensity to seismic activity and its base of basalt and tuff rock formations, known for high permeability and instability, made the need for construction and engineering protocols essential. Due to tight budgetary and timeline restrictions, developers bypassed critical measures that would have ensured a solid foundation before backfilling. Furthermore, engineers should have considered the dam’s unique location and environmental conditions while developing the design. The decision not to grout fissures to keep the soil used in the core from settling was a fundamental ecological and design lapse that led to internal erosion and subsequent collapse.

Written by Mark Breske

Of all the notable figures in Idaho’s history, Polly Bemis stands out as one of the most resilient and memorable. Polly Bemis was born in northern China in 1853. In 1872, she was smuggled to the United States and sold as an enslaved person in San Francisco for $2,500. From San Francisco, Bemis was escorted to Portland, Oregon, and eventually settled in Warrens, Idaho Territory (now Warren) with her Chinese owner. Polly earned a reputation in the small community for her clever, pragmatic, and kind personality. While it is uncertain how Polly eventually acquired her freedom, a census shows Polly living with her future husband, Charlie Bemis, in the mid-1880s. Charlie had called Idaho home since roughly 1866 and made a name for himself in Warren as a merchant, miner, saloon owner, and boarding house operator.

Charlie and Polly formed an intense bond. It’s been noted that Charlie often saved Polly from harassment at the saloon. Polly returned the favor by, nursing Charlie back to health after he was shot in the face following a disputed poker game. Polly would again save his life when their home caught fire in 1922. Polly and Charlie married on August 13, 1894, in their home, which was also Charlie’s saloon. The couple soon filed a mining claim along the Salmon River near Warren, where they mined and established a small farm. Polly grew an array of fruits and vegetables and raised chickens, ducks, and cows. Polly was known to sew, crochet, and fish in the nearby river.

Polly and other Chinese immigrants of her time were never considered American citizens due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and its extension, the Geary Act of 1892. The legislation prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers. It also required Chinese immigrants to apply for a certificate of residence and always carry it with them if they wished to stay in the United States. In remote Warren, Polly had been promised assistance in filing for her certificate by George Minor, an IRS collector. Minor failed to make the journey due to impassable winter roads leaving Polly at risk of deportation. In 1896, Polly and roughly fifty other Chinese migrants appeared in the Moscow district court to petition for their certificates. She was successful and lived in Idaho until her death in 1933.

By 1920, Charlie’s health had steadily declined. He passed away shortly after suffering severe burns in the fire that destroyed their Salmon River home. Polly returned to Warren, and with the help of friends, she rebuilt their home and lived along the river by herself for over a decade. Later in life, Polly left the Warren area and was often amazed by the glimpses she got of bustling towns and cities. Regional newspapers reported Polly’s wonder at seeing a railroad for the first time, riding in a car, and even watching her first movie. Weeks after a stroke, Polly died on November 6, 1933, at the age of 80.

The National Park Service listed the Polly Bemis Ranch in the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. The 26-acre property is surrounded by 2.2 million acres of the Frank Church Wilderness Area, the largest protected wilderness area in the continental United States. During her lifetime, Polly Bemis was respected for her welcoming, bright, and mischievous personality. Today we also see her story as one of true Idaho resilience.

Written by Nicole Inghilterra and Mark Breske

As we head into the holidays, learning about the traditions at the Old Idaho State Penitentiary offers us a chance to reflect on our own holiday experiences. Thanksgiving at the Idaho State Penitentiary was welcomed by many who were serving time at the site. But, for some incarcerated men and women, the holiday season was a painful reminder of the distance and isolation from family. However, it is not all a loss of hope and a time of despair. The inmate-produced prison newspaper The Clock is an excellent source of insight into the monthly experiences of incarcerated individuals at the site. Nearly every November issue of The Clock featured updates from the dining hall and what to expect for the annual Thanksgiving meal. The holiday issues also usually included articles written by the chaplain and contributing writers about giving thanks. It was a treat for the men working in the dining hall and kitchen to prepare a special meal for everyone else.

The dining hall was built in 1898 and was the first building designed and constructed entirely by prisoners. George Hamilton designed the dining hall and oversaw its construction. The ground floor held space for the dining room, a kitchen, and the bird’s nest. An armed guard sat in the bird’s nest to watch over meal times. Down below, the basement had six rooms. Initially, there was a bakery, a root cellar, bathing facilities, a butcher shop, a laundry room, and a shoe shop within the space. The riot of 1973, which led to the site’s closure, caused the building to go up in flames, leaving just the exterior walls standing today.

By the 1950s, the Idaho State Penitentiary was largely self-sufficient in almost every aspect. Under the wardenship of Louis E. Clapp, the pen flourished in the growth of rehabilitative initiatives and vocational industries. Farming was always one of the industries tied to the site, but it grew with Clapp at the helm. There were three major areas where men cultivated land: the penitentiary grounds, Moseley Ranch (now Warm Springs Golf Course), and Eagle Island Prison Farm (now Eagle Island State Park). The food the farms produced was enough to keep the dining hall and bakery stocked, provide a reserve for the prison’s use, and feed residents at State Hospital South in Blackfoot. The prison sold any remaining surplus back into the community.

In the November 1959 issue of The Clock, an article titled “The Life Line” described statistics surrounding meal production in the dining hall basement during–and outside the holiday season. The dining hall would feed about 350 men in a half hour, three times per day. Most kitchen and bakery staff would work 7-hour days, sometimes longer, especially around the holidays. The bakery went through 1,300 pounds and 60 dozen eggs per week, which the prison farm chickens provided. Inmates processed vegetables in the root cellar; according to the article, workers processed about 3,000 pounds of potatoes per week! Between the biennium of 1959 and 1960, workers processed 680 turkeys, and inmates consumed 399,182 potatoes. The men working in the kitchen took pride in what they did and especially looked forward to providing a good holiday meal.

Though the menu in 1959 wasn’t published in the November issue of The Clock, the November issues in 1956 and 1971 had robust offerings. Menu items included roast turkey, sno-flake potatoes, giblet gravy, creamed peas, buttered corn, cranberry jelly, tossed salad, stuffed celery, hot rolls, creamed pumpkin pie, and hot coffee.

The Nez Perce War stemmed from an escalating land conflict between several bands of the Nez Perce Tribe and the United States government. The 1863 Treaty, known as the ‘Thief Treaty’ by the Nimiipuu, outlined the conditions that would eventually lead to an all-out war between the Nez Perce and the US Army in 1877. The treaty era for the Nez Perce began in 1846 with the creation of Oregon Territory. Westward expansion immediately made land in the northwest more of a commodity, so much so that in 1855, territorial governor Isaac Stevens met with tribal representatives to negotiate the tribe’s surrender of 7.5 million acres of land in exchange for hunting and fishing rights. The US Senate ratified the treaty in 1859.

When gold was discovered along the reservation’s boundaries in 1860, the US government drafted another treaty to further shrink the reservation by absorbing another five million acres of reservation lands, which became the 1863 Treaty. By 1869, reservation lands were reduced to just 750,000 acres in Idaho Territory. All Nez Perce members were ordered to move onto smaller reservation land east of Lewiston. Many tribal members defied the order and remained on their lands.

Disputes between white landowners and tribal members continued to escalate. In May 1877, General Otis Howard ordered non-treaty tribal members to move to the reservation within 30 days. By June, 600 Nez Perce members gathered on the Camas Prairie, where warriors began war ceremonies. Warriors then acted against four white men in a raid. Chief Joseph and his brother Ollokot arrived at the camp the next day to find out what had happened. Joseph knew an attempt at peace was futile at this point as General Howard moved 130 men to the reservation to retaliate. The military underestimated the power of the Nez Perce and was defeated in the Battle of White Bird Canyon on June 17, 1877, thus beginning the Nimiipuu’s escape eastward from US soldiers. A small band of Nez Perce warriors slowed military efforts amidst the retreat from Idaho into Montana Territory. Brigadier General Nelson Miles led a surprise attack on the Nez Perce camp on the morning of September 30. On October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph surrendered at the Bear Paw battlefield in Montana Territory with one of the most infamous speeches in US history: