The Capitol Curation Program is the product of a partnership between the Idaho State Historical Society (ISHS) and Idaho Capitol Commission. The Capitol Curator preserves and promotes the historic character of Idaho’s statehouse and manages a collection of over 1,000 artifacts and historic furnishings connected to the Idaho State Capitol. Through permanent and temporary exhibits within the capitol, the program provides context for this iconic monument and the place of government in the lives of Idahoans.

Make your visit to the Idaho State Capitol more meaningful with Idaho Landscapes: Temple of Light. This special edition of the Idaho State Historical Society’s publication series guides you through the capitol’s construction, history, and 21st century restoration. The booklet is available in the Idaho State Capitol Gift Shop.

Artifacts of the Idaho State Capitol

On the Capitol Mall Grounds

At 09:37, September 11, 2001, two Idahoans were lost in a terrorist attack that changed our nation and ignited America’s longest war. Navy Lieutenant Commander, Ron Vauk, graduate of Nampa High School, and presidential management intern, Brady Howell, of Sugar City, Idaho, were killed when American Airlines Flight 77 struck the west side of the Pentagon. Vauk and Howell became the Gem State’s first casualties in the War on Terror. In the following years, many Idahoans would join them while serving their county.

On September 11, 2010, Brig. Gen. Allan C. Gayhart, Assistant Adjutant General-Army and a crowd of hundreds gathered to establish a memorial honoring their sacrifice. The commemorative pavilion at the entrance to the Old Ada County Courthouse features two pillars listing the fallen who once called the Gem State home. What began as a roll call of 17 men and women across military and civilian service has now grown to include 66 names.

These losses are never easy. This memorial, at the heart of our capital city, gives us a chance to come closer to Idahoans who can never be forgotten. It is my hope that their names do not only mark this stone but are engraved on the hearts of Idahoans made safer by their sacrifice.

“I worked so hard to get here, and I am proud of what I do.”

Brady K. Howell

1975-2001

Erected in 1935, the Grand Army of the Republic Monument is a small stone that carries a big message.

Founded by former Union soldiers, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a benevolent organization that supported Union veterans of the Civil War. Among their many projects, the GAR paid for veterans’ medical care, advocated for legislation, and established monuments to soldiers lost in the war.

Though membership was limited to men, women formed an auxiliary group named the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic. This group is credited with the 1935 donation of the monument at the Capitol.

When President Abraham Lincoln appointed Republican allies to serve in Idaho Territory, it created a distant haven for Union soldiers. Many Union veterans relocated to Idaho, bringing the GAR with them. The many GAR Posts throughout the state demonstrate the prevalence of membership across Idaho’s citizenry.

A GAR meeting hall named Phil Sheridan Post No. 4 sits directly in sight of the monument. This building is on the National Register of Historic Places. “Lovingly erected and dedicated by the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic,” the monument honors, “the Grand Army of the Republic who…kept all the stars in the flag and the United States of America on the map of the world.”

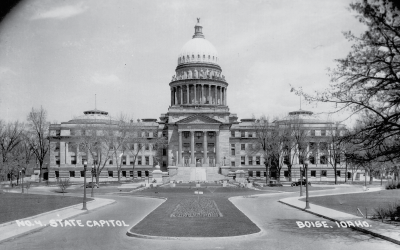

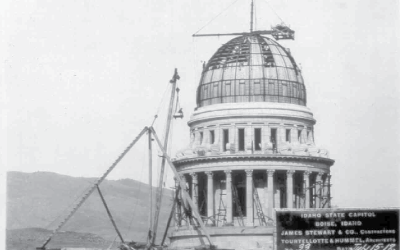

The Idaho State Capitol building radiates the ideals of democracy. The building’s Beaux-Arts and Neoclassical features contribute to its sense of grandeur and steadfastness. Small details and ornaments breathe life into architects John E. Tourtellotte and Charles Hummel’s vision to “make clear the path of duty.”

The most visible of these symbols is the five-foot, seven-inch tall eagle perched on top of the building’s central dome. The Capitol’s eagle, symbolizing strength and freedom, stands as an emblem of the nation. It also connects Idaho’s government with the state’s place in U.S. military history.

With the decommissioning of the USS Idaho (BB-24) in 1914, the Gem State received mementos of the Idaho’s namesake battleship. In 1942, Idaho State Historical Society Board of Trustees President Frank Martin inquired into the history of the iron and bronze figurehead that featured on the ship’s prow. His research on this piece led to an unexpected discovery—the copper eagle perched on top of the Idaho State Capitol also derived from parts of the battleship.

As late as 1913, drawings and photographs placed the nation’s flag or other elements atop the lantern dome, making it unclear when exactly the eagle became part of the Capitol. In 2005, during the building’s expansion and restoration, an artisan adorned the eagle with fresh gilding of gold leaf, revitalizing the grandeur of this iconic democratic symbol for decades to come.

The story of Merriwether Lewis and William Clark’s 1804-1806 expedition has long captivated Idahoans. In truth, Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery put Idaho on the map for the United States, an effort that could not have been successful without the help of Native American tribes.

Doug Hyde’s Hospitality of the Nez Perce interprets the moment the explorers and Nez Perce first crossed paths. Wrought in bronze, Chief Twisted Hair, known by his people as Walamottinin, offers guidance to Lewis and Clark. The chief’s son Lawyer, also called Hallalhotsoot, plays with trade goods at their feet.

The meeting is peaceful as there is a child present, and the boy is relaxed and curious. Lewis and Clark are receptive to the chief’s information and appear as equals with their host, though culture still divides. Lewis appears unaware that his single pointed finger may be misunderstood by the Nez Perce while Walamottinin gestures with a more personally respectful two fingers.

By the time of their arrival in Nez Perce lands during the fall of 1805, the expedition was exhausted. Fresh from a grueling trek through the Bitterroot Mountain, they spent several days with Walamottinin as they resupplied and familiarized themselves with the landscape ahead.

A descendant of the Nez Perce, Assiniboine, and Chippewa peoples, Hyde grew up in Idaho. His first cast of Hospitality of the Nez Perce is displayed on the campus of Lewis and Clark State College. This second cast was commissioned by Carol MacGregor, PhD, for the Capitol Mall. In 2006, she presented the piece to the state of Idaho as a reminder of these early encounters with the Gem State’s first peoples.

The Idaho Women’s Suffrage Commemorative Sculpture embodies the spirit and legacy of the women’s suffrage movement and universally represents Idaho women through time. This nameless woman walks metaphorically in the footsteps of those who came before and then hands off her shoe to the future. The sculpture’s placement on the grounds of the People’s House is a statement of the importance of women to our state.

In 1950, the U.S. Treasury Department selected the Liberty Bell, one of America’s most recognizable symbols, as the emblem for its Savings Bonds Independence Drive. In Annecy-le-Vieux, France, the Fonderie Paccard cast the replicas, and President Harry S. Truman shipped them to every state and most U.S. Territories.

Idaho’s bell toured the state in early 1950 before coming to its permanent home at the Idaho State Capitol. As co-chairman of Idaho’s U.S. Savings Bond Division, T. H. Wegener officially presented the bell to Governor C.A. Robins on July 5, 1950.

The original Liberty Bell began its life as a signal. Cast by metalworkers John Pass and John Stow in 1753, the bell of the Pennsylvania State House knelled to mark major events. For decades, Pass and Stow’s bell signaled the start of official business as well as the rise and fall of British monarchs. Muffled to protest the passage of the Stamp Act and triumphantly rung at its repeal, the bell began to take on new meaning as part of a growing movement for liberty central to the American Revolution.

After many years of heavy use, the bell cracked, and in 1846, Philadelphia paid for repairs. Sadly, preventing further damage also silenced the bell forever. Over time, the bell and its inscription, “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land Unto All The Inhabitants Thereof,” became a rallying cry for groups seeking liberty. Abolitionists first drew inspiration from the inscription, and in the 19-teens, Pennsylvania suffragists cast a replica Liberty Bell to symbolize their cause.

At the entrance to the Capitol Mall, President Abraham Lincoln, “The Emancipator,” stands atop a sandstone base. Donated to the State on February 12, 1915, by the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic, the statue originally stood in front of Lincoln Hall at the Idaho Soldiers Home. The oldest statue of Lincoln in the Western United States, it was moved to the new Idaho Veterans’ Home in the Fort Boise campus in the 1970s.

In 2009, the Idaho Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission moved the statue to the Capitol mall in honor of the 200th anniversary of the President’s birth. Idaho children donated 500,000 pennies to finance the relocation and conservation. At its current iconic location, the piece is a reminder of Lincoln’s central role in creating and shaping Idaho Territory.

Seven such images were designed by sculptor Alfonso Pelzer. Lincoln’s face was modeled after the President’s original 1860 life mask. It is fabricated of two-ounce sheet bronze with a sandstone base quarried from nearby Table Rock. A selection from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural is incised on its North façade. The East side of the base declares: “More than any other state, Idaho is related to Abraham Lincoln.”

The President holds a partially unrolled copy of the Emancipation Proclamation in his left hand. A careful observer will note that Lincoln stands offset to face West. The angle emphasizes the impact of his policies and actions on Idaho and the Rocky Mountain states, even amidst the Civil War.

When visiting the Idaho State Capitol and the surrounding grounds, there is so much to take in! Between the building’s grand architecture and the many nearby memorials, it is easy to miss some of the little details, especially those beneath your feet.

Embedded in the pavement at the intersection of Capitol Boulevard and Bannock Street, near the base of the Abraham Lincoln Memorial, a small bronze plaque pays tribute to the beloved President’s often overlooked career as a land surveyor.

Compared to his time as an attorney and politician, Lincoln’s work as a surveyor is not widely known. After the failure of Lincoln’s first campaign for state office, a friend invited him to help with a survey of Sangamon County, Illinois, in 1833.

Lincoln quickly dove into learning the trade. Through a combination of his characteristic penchant for self-study and the tutelage of schoolteacher Mentor Graham, Lincoln mastered the skills required to document the landscape that surrounded him. Even after his election to the state legislature in 1834, Lincoln continued to conduct land surveys until 1836.

The cannon on the Capitol lawn has an obscure history and evidence of its service record is difficult to find. Some say the cannon was used at the Battle of Vicksburg during the Civil War, others suggest it never saw combat. We do know that this Model 1845 Sea Coast Gun has had a colorful history within the Gem State.

Installed on Capitol Grounds in 1910, the cannon was originally accompanied by a pyramid of cannonballs. Over the years, the stack diminished as pieces were taken by passers-by, and eventually, the remaining balls were removed.

Officials commissioned a custom masonry base preventing unscrupulous parties from moving the several thousand-pound weapon. Although it is a functional piece of artillery, the cannon’s barrel is now filled with cement.

Unsanctioned explosions at the cannon were common and most often credited to local teenagers. According to local lore, it served as a drop site for Prohibition-era bootleggers. In the 1950s, The Idaho Daily Statesman recalled that the High Desert sun-heated a bottle of alcohol stashed inside the barrel until it exploded. A compelling story, but proof of the event is hard to find.

In the 1940s, Governor Chase Clark wanted to “scrap” the cannon for the war effort. Outcry from the community – most notably members of the local Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic chapter – stopped the proposal, and the cannon remains to this day.

The Pioneer Monument, the Capitol grounds’ oldest memorial, was erected in 1906. Created to “perpetuate the memory of the old Oregon trail,” Ezra Meeker, a veteran pioneer, led efforts to establish this and many monuments along the historic Oregon Trail.

Motivated by his fear that U.S. pioneer history would be lost, Meeker dedicated much of his later life to memorializing the route that changed the western United States. To raise funds for the monument on the Capitol grounds, Meeker was reported to have driven his wagon team to each of Boise’s schools. Thousands of children contributed pocket change to the effort.

In 2006, exactly 100 years after the monument’s installation, state and city politicians gathered on the lawn with hundreds of school children to unveil a time capsule that had been buried at the monument’s base. To the disappointment of many, nothing was found. It was later discovered that the time capsule had been removed in 1984 following an incident in which a tractor crashed into the monument’s obelisk.

Meeker’s mission to educate others on pioneer history has been carried forward, with even more tributes have been added in recent years. Today, the Pioneer Monument stands as a symbol of the countless lives changed by western migration along the Oregon Trail and the perseverance of one person to ensure others remember their history.

Arguably one of the most well-known Idahoans in history, William E. Borah rose to national prominence in 1906 with his prosecution of “Big Bill” Haywood following the assassination of former Governor, Frank Steunenberg. His role in the “Trial of the Century” earned Borah a reputation as a captivating orator.

Though Haywood was acquitted, Borah successfully ran for public office and served Idaho in the U.S. Senate for more than three decades. By the time of his death in 1940, Borah was recognized throughout the nation as a constitutional scholar and complicated individual who strove to do what he thought was best for the people of the Gem State.

As graduates of Borah High School, named in honor of the senator, we two friends feel a deep connection with the “Lion of Idaho.” We hoped a prominent statue of this political titan would help educate Idahoans and beautify the Capitol Mall.

We selected Idaho sculptor Irene Deely to design and create an arresting 8-foot-tall image of Borah. While we two funded the project, David Leroy helped arrange its placement. The finished piece stands purposefully in front of Boise’s Old Post Office. Now known as the Borah Building, the structure officed Idaho’s Congressional Delegation for many years.

Standing beside this bronze memorial is like being transported back in time. One is suddenly walking down Jefferson Street alongside Borah on his way to his office, ready to correspond with luminaries from Carrie Chapman Catt to W.E.B. Dubois.

On January 28, 1986, I watched the Space Shuttle Challenger explode alongside millions of Americans across the nation. I thought a dream had died in the disaster with Christa McCauliffe and her fellow crewmembers. As part of the Teacher in Space program, I trained as Christa’s backup hoping to send an educator beyond our planet.

Treasure Valley teens, Ralston, Timothy, and Jason Fuhriman understood that Idahoans needed a way to commemorate space explorers who never returned. Shortly after the tragedy, they decided to build a monument for the Capitol Mall. The brothers were Boy Scouts and structured the project to earn their Eagle Scout rank.

Ralston worked with a local stonemason leading construction of the brick pedestal. Tim collaborated with a metalworker at Boise State University to create its statue. Jeremy planned the memorial’s dedication and placement of a time capsule to be opened on the 100th anniversary of scouting.

Roughly a year after the Challenger disaster, the boys and their fellow Scouts unveiled the memorial which also paid tribute to the Teacher in Space Program. Christa’s and my dreams for the program came true in 2007. On the Space Shuttle Endeavor, I became the first educator to leave our pale blue dot.

The time capsule was opened in 2010 and the monument updated. Scouts added a new capsule and a plaque memorializing the 2003 crew lost in the Space Shuttle Columbia. Today, the monument reminds Idahoans of those who sacrificed all to carry humanity to the stars.

A stately bronze statue stands atop a granite base in memorial to Governor Frank Steunenberg, one of only five governors to have been assassinated in the United States. Nearly five years after leaving office in 1901, Steunenberg was killed by a bomb at his home in Caldwell.

The man who planted the explosive, Harry Orchard, was captured shortly after. Orchard alleged he had been hired by leaders of the Western Federation of Miners to commit the crime as retribution for Steunenberg’s handling of union protests in north Idaho.

“He paid for his devotion to his ideals with his life… The vengeance of the labor unions…followed him for five years until the opportunity for action presented itself.” (Idaho Statesman, December 11, 1927, p. 12)

The trial against Orchard’s alleged co-conspirators gained national attention. Potential conviction of union members amplified the ongoing struggles between workers and corporations throughout the nation.

Yet, even before the trial commenced, Steunenberg’s friends and fellow Idahoans wanted to ensure that his memory was preserved. Formed in 1906, the Steunenberg Memorial Association worked for more than 20years to honor the former governor. Sculptor Gilbert Riswold of Salt Lake City, Utah, was awarded a $25,000 contract to create the statue in Steunenberg’s honor.

On December 11, 1927, the memorial was presented to the state. Steunenberg gazes at the Capitol that had only just broken ground at the time of his death. His visage has become an arresting symbol of a tumultuous moment in Idaho’s past.

Inside the Capitol

Gem State citizens and travelers alike have been captivated by the architecture of Idaho’s Statehouse since the building’s completion in 1920. Lionel D. Jolly was one such man though he lived beyond Idaho’s borders. After years of extensive travel, Jolly came to see the architecture of each capitol as an illustration of “the values and time period in which it was built.”

In 1981, Jolly encountered the work of artist Robert Allen. An engraver and etcher, Allen’s process used chemicals to create unique textures and patinas. He would then use dental tools to illustrate his subjects in exquisitely vibrant detail.

Jolly commissioned Allen to produce an engraving of each state’s capitol building as part of the “America’s Heritage State House Project.” With Allen’s guidance, Jolly photographed the building as source material for the work.

Though Jolly passed away in 2001, he established a trust to continue the project. 28 years after the partnership began, the last of 50 etchings was completed in 2009. Jolly hoped that Allen’s work could be displayed within the capitols they depicted. His estate honored his wishes by donating each piece to their respective state.

In 2011, the Lionel Jolly Trust donated Allen’s rendition of our Capitol of Light to the State of Idaho. Since it’s addition to the Capitol Collection, the etching has been displayed throughout the statehouse and is currently exhibited in the Governor’s Ceremonial Office.

Over 150 years after his death, President Abraham Lincoln continues to inspire Idahoans. From portraiture to literature, Lincoln’s legacy extends across mediums and throughout time. In creating his sculpture series, Dancers who Dance Upon Injustice, Dean Long Estes saw a creative spark in the face of our sixteenth president.

As one of the first presidents to be consistently photographed throughout his time in office, the transformation of Lincoln’s well chronicled visage tells the story of his presidency and one of America’s most trying moments. Titled Abraham Lincoln “Democracy,” Estes depicted a craggy, deeply lined face, careworn from the struggle of Civil War. Yet he also captured the strength and drive of the man himself.

Of the 24 busts in Estes’ series, several were installed for public display throughout the state. In 2016, the Ada County Lincoln Day Association purchased this piece with the intent to showcase it at the Association’s annual banquet. Committee members offered the piece for exhibition in the Capitol when it was not being used by the Association.

Today, the bust is appropriately housed in the Lincoln Auditorium, a space re-named in 2013 at Idaho’s Territorial Sesquicentennial. Every February, the Association brings the bust to its Lincoln Day festivities and returns it to the Capitol where the public can get a closer look at the face of a president who never fails to inspire.

At the heart of the Capitol, its cavernous rotunda reaches up to the sky, capped by a double layered dome. This construction is as much practical as it is decorative. Early 20th century architects designed the interior dome to funnel hot air up through the building into the attic of the exterior dome. Once opened, exterior windows would vent the building helping to maintain a mostly comfortable temperature in an era before air conditioning.

Within the oculus, or “eye” of the dome, hangs a painted disc covering the underside of the exterior dome. 11 feet in diameter, the hand painted and gilded shield symbolizes Idaho’s place in the constellation of United States. 13 large stars represent the original American colonies that banded together to become our nation. 43 smaller stars call out Idaho as the 43rd state in the union.

During the 21st century restoration (2007-2010) each star on the sky-blue disc was painstakingly repaired. The gilding that gives them their characteristic sheen was reapplied by hand. Artisans stood on scaffolding suspended roughly 150 feet above the marble compas rose on the rotunda’s first floor.

A stairway, barely visible from below as the rectangular drop in the oculus disc, carries you up and into the highest reaches of the building. From this vantage, with nearly the full breadth of Idaho’s capital city in view, it’s easy to see that we truly are the Gem State.

When the restored Capitol reopened in 2010, a mosaic on the building’s new Garden Level was revealed. Measuring 12 feet in diameter, 53,823 individual glass tesserae depict Idaho’s State Seal. However, the version gracing the Capitol floor bears marked differences from Emma Edwards’ original 1891 design.

In 1957, under the direction of the State Legislature, Paul B. Evans, a Caldwell artist from Caxton Printers, Ltd., revised the seal. Evans significantly changed the shape of the woman, modified the miner’s clothing, and contributed additional details he felt modernized the seal. Just as Edwards interpreted her own time in the original design, Evans’ variation reflects the trends of the 1950s.

Evans’ version was adopted as the official state seal of Idaho, and for over three decades, acknowledgement of Edwards’ contribution was often left out of the discussion surrounding this central Gem State symbol. At the Statehood Centennial in 1990, historians and advocates for Idaho heritage petitioned the Legislature to ensure credit for the seal would be attributed to each artist. Senate Bill 1339 was signed into law in 1994, placing both names on all official copies of the Great Seal of the State of Idaho.

One of our Statehouse’s most profound artifacts is Charles Ostner’s George Washington Equestrian Statue. Ostner came here from far beyond our region. Drawn to Idaho Territory by the mining boom of the 1860s, he laid down roots in the Treasure Valley and earned a reputation as an architect and artist.

The story goes that the Austrian immigrant carved George Washington from a single pine tree. With a postage stamp to guide him, Ostner took four years to create his masterpiece. His young son was said to have frequently held a candle to light his workroom after darkness fell.

Once completed, Ostner gave his rendition of our first president to the Territory in 1869. In return, Idaho’s leadership paid him $2,500. Displayed on the grounds of the Territorial Capitol building, the statue weathered after decades of exposure outside. Once restored and brought inside the State Capitol it was gilded. Ever since, it has stood as a reminder of our nation’s earliest days.

I can only imagine what went through Washington’s mind as he brought America from a revolutionary force to nation. He certainly believed that those of us serving our fellow citizens all have a part to play in overcoming the challenges we face. As he said in his 1756 address to his officers in Virginia: “Remember that it is the actions, and not the commission, that make the officer, and that there is more expected from him, than the title.”

Since 1919, this desk has been used by each of Idaho’s highest executive officers. A fixture of the Governor’s Ceremonial Office, this central piece of furniture is both symbolic and functional. Called a “partner’s desk,” the desk is designed for use by two people. The officeholder and their colleague can sit at each side to address matters of state.

Inspired by British library tables used in the 1700s, large two-seater desks became a popular choice with the rise of middle-class businesses. With collaboration at the heart of its purpose this ceremonial desk speaks to the way in which Idaho governors have led the state for well over a century.

Carved from Spanish mahogany and fitted with brass accents, the desk replaced a roll top model that had been used by Idaho leaders in the Territorial Capitol building. At the Capitol’s openings in 1913 and 1921, furniture for the building was commissioned by a small handful of companies. The Wollaeger Manufacturing Company constructed the bulk of the furniture and many of the sturdy pieces are still in use today.

During the Capitol’s 2007-2010 restoration and expansion, the Idaho State Historical Society identified the building’s original furniture. The Capitol Commission funded their restoration for use throughout the statehouse. Today they serve as a touchpoint to the way our Capitol of Light would have looked when its doors first opened to Gem State citizens in 1921.

John E. Tourtellotte and Charles F. Hummel embedded exquisite detail throughout Idaho’s Capitol of Light. Artisans used rare materials to create a structure that is now priceless and irreplaceable.

Within the central section’s North Wing, then home to the Idaho Supreme Court, function and form merged in the hand painted clock above the justices’ bench. Built into its niche, designers likely hoped the timepiece would count down the minutes of oral arguments and judicial deliberations for generations to come.

However, within 30 years of the Capitol’s opening, the clock had been hidden from view and painted with an image of the scales of justice over a legal tome. The rationale for this decision has been lost to time, but an unfortunate incident reintroduced Idahoans to the North Wing clock.

On New Year’s Eve of 1992, cigarette embers in the Attorney General’s Office ignited a blaze in the building’s North Wing. The next afternoon, a security guard pulled the fire alarm (no smoke detectors had sounded) and crews doused the flames. Damages were assessed at more than $3.2 million. During the recovery, the clock was rediscovered and restored to its former glory.

In many ways, the fire lit the spark for the Capitol’s restoration. So much had gone wrong. Yet, rebuilding after the disaster gave Idahoans a chance to see how the Capitol could be transformed into a safe and functional space that stayed true to the grandeur its original architects envisioned.

John E. Tourtellotte and Charles F. Hummel embedded exquisite detail throughout Idaho’s Capitol of Light. Artisans used rare materials to create a structure that is now priceless and irreplaceable.

Within the central section’s North Wing, then home to the Idaho Supreme Court, function and form merged in the hand painted clock above the justices’ bench. Built into its niche, designers likely hoped the timepiece would count down the minutes of oral arguments and judicial deliberations for generations to come.

However, within 30 years of the Capitol’s opening, the clock had been hidden from view and painted with an image of the scales of justice over a legal tome. The rationale for this decision has been lost to time, but an unfortunate incident reintroduced Idahoans to the North Wing clock.

On New Year’s Eve of 1992, cigarette embers in the Attorney General’s Office ignited a blaze in the building’s North Wing. The next afternoon, a security guard pulled the fire alarm (no smoke detectors had sounded) and crews doused the flames. Damages were assessed at more than $3.2 million. During the recovery, the clock was rediscovered and restored to its former glory.

In many ways, the fire lit the spark for the Capitol’s restoration. So much had gone wrong. Yet, rebuilding after the disaster gave Idahoans a chance to see how the Capitol could be transformed into a safe and functional space that stayed true to the grandeur its original architects envisioned.

In the 1960s, Bank of Idaho commissioned this painting of Idaho’s Territorial Capitol from Boisean Quinten Gregory. Gregory was a successful artist, known for his realistic paintings and the instructional videos he created to teach his craft to others. This painting was eventually purchased by William Campbell and was donated to the Gem State at its centennial in 1990.

The subject of the piece once stood where the East Wing of the Capitol is today. Finished in 1886, the four-story, red brick structure was designed by Detroit architect Elijah E. Myers. Meyers had amassed an impressive portfolio as the architect behind several capitol buildings across the United States.

The building served as the base of Idaho government for 24 years. Even after the central section of the State Capitol was completed, the Territorial Capitol continued to house state agencies such as the Idaho State Historical Society. Once construction began on the State Capitol’s wings 1919, the Territorial Capitol was demolished.

This unique piece bridges the gap between so many different times in Idaho’s capital city. From the late 19th century when the Territorial Capitol was finished, to the changing city of the 1960s, and even the celebration of 100 years of statehood in 1990. Quentin’s piece is a fitting tribute to the Gem State’s first dedicated hall of government.

Outside the Lincoln Auditorium hangs a large chromolithograph painting of the 16th President of the United States. This 1863 portrait of Abraham Lincoln in its original frame was once owned by John Wanamaker (1838-1922) of Philadelphia, the man credited with inventing the modern department store.

Wanamaker first met the president-elect in 1861 when Lincoln was traveling to Washington, D.C. for his inauguration. On June 16, 1864, Wanamaker was introduced to Lincoln again when the President returned to Philadelphia raising money for Civil War soldiers, widows and orphans. Inspired by these encounters, Wanamaker later lectured and wrote about President Lincoln. In 1908, he published a book called “The Wanamaker Primer on Abraham Lincoln.”

This portrait remained in the fifth-floor executive offices of Wanamaker’s Department Store until the 1970’s when it was purchased at a public sale. In 1992, it was rediscovered leaning against a chair on the lawn of a rural Pennsylvania antique store during a light rain. I purchased the piece and shipped it to the nation’s capital where it was displayed in the federal agency offices of the United States Nuclear Water Negotiator.

For the 2013 Sesquicentennial of Idaho Territory, my wife, Nancy, and I donated the Wanamaker Portrait to the State of Idaho. Its prominent placement outside the Lincoln Auditorium links Idaho citizens to a man who twice shook the hand of President Abraham Lincoln.

The original Winged Victory of Samothrace was created in the second century BCE. Carved from Parian marble, the figure of Nike, Greek goddess of victory, was recovered on the island of Samothrace in 1863 by Charles Champoiseau, of France.

Upon its arrival in Paris, the statue became an iconic part of the Louvre Museum. At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Winged Victory was removed to prevent her destruction. When peace returned, she was placed back on display but the country outside the museum was in dire straits.

Citizens across the United States initiated a grassroots effort to send food, clothing, and financial aid to France and Italy. Approximately 700 boxcars full of $40 million worth of supplies made their way across the Atlantic for distribution throughout the two nations.

In response to the “American Friendship Train,” the people of France started their own movement to fill a “Merci Train” with gifts of thanks for American aid. From children’s drawings to wallpaper, housewares to military medals, forty-nine “Forty-and-Eight” boxcars (named for the forty men or eight horses that could fit in each car) were filled and readied for distribution to each state.

No two boxcars were the same. When Idaho’s boxcar arrived on February 22, 1949, Idahoans found this stunning plaster cast of Winged Victory of Samothrace inside. Today, Nike stands outside of Statuary Hall as a reminder of the Gem State’s connection to the world around us.

HOURS

Monday-Friday | 8 pm-5 pm

Saturday | 9 am-5 pm

LOCATION

700 W. Jefferson St.

Boise, ID 83702

CONTACT INFO

(208) 332-1826

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Idaho State Capitol Permanent Exhibits

Governing Idaho: How People and Policy Shape Our State, located in the Garden Level Rotunda, is the Idaho State Capitol’s signature permanent exhibit. In 2011, the project won the American Association of State and Local History Award of Merit. Learn how the Idaho State Capitol came to be. Explore the history of state government with interactive challenges. Become inspired to actively participate in leadership and governance of the Gem State. Brochures accompanying the exhibit can be found in the Idaho State Capitol Gift Shop.

Winged Victory of Samothrace was gifted to the state of Idaho by the people of France as part the Merci Boxcar Train following World War II. The statue is a magnificent replica of the Louvre’s 2,000-year-old marble masterpiece. Discover more about Winged Victory’s journey to Idaho and the Merci Boxcar Train at the 4th floor rotunda entrance to Statuary Hall.

The George Washington Equestrian Statue was presented to the Territory of Idaho by artist Charles Ostner in 1869. Learn about this Idaho pioneer and his iconic work at the 4th floor rotunda entrance to Statuary Hall.

The Lincoln Auditorium is a functional space within the capitol enriched by artifacts and ephemera connected to President Abraham Lincoln. Displays at the entrance and back of the auditorium were created in partnership with David Leroy to honor President Lincoln’s legacy in the Gem State.

Portraits of Idaho Governors and Legislators have been reproduced and displayed throughout the capitol. Governors’ portraits from 1890 to the present hang outside the 2nd floor entrance to the Governor’s Office. Legislative composite photographs can be viewed throughout the Garden Level East and West Wings, as well as the 3rd and 4th floors of the capitol.

Temporary Exhibits

Roots of Capitol History

In memory of the late Representative Max Black’s contributions to the Gem State, the Idaho State Historical Society and Idaho State Capitol Commission are proud to present the exhibit, Roots of Capitol History in Statuary Hall. In 2007, the Statehouse underwent a comprehensive restoration and expansion. Many of the historic trees had become unstable or conflicted with building plans. Representative Black partnered with ISHS to distribute their wood to Idaho woodworkers, hoping they would transform each piece into art for the people. Roots of Capitol History showcase the tale of the Statehouse’s historic trees and the creative spirit of Idahoans.

Mapping the Gem State

LaFayette Cartee came to Idaho in 1863, the same year President Abraham Lincoln established the territory. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Cartee to serve as Idaho’s first Surveyor General to map the newly created territory. Currently on display in the East and West Wings of the Capitol’s Garden level, Mapping the Gem State showcases Cartee’s work. Each painstakingly drawn map provides insight into the evolving story of the region’s land and people. Explore a selection of Cartee’s surveys from the Idaho State Historical Society collections and learn more about the man behind the maps.

On January 9, 2010, the Idaho Statehouse, “A Capitol of Light,” was rededicated after three years of restoration. In partnership with the Idaho Capitol Commission, the Idaho State Historical Society (ISHS) played an active role in this restoration project.

Throughout the restoration the ISHS:

- Inventoried and analyzed the condition of all artifacts removed from the capitol.

- Conserved and reproduced all legislative portraits and composites. Framed reproductions were then rehung in the extended Garden Level Wings and throughout visitor galleries. Original materials are now preserved in the Idaho State Archives.

- Identified, examined, and restored over 560 historic furnishings and objects from the capitol building which formed the basis of the Capitol Collection.

- Reproduced and curated historic photographs from the Idaho State Archives complimenting the historic character of the building and highlighting the function of committee spaces.

- Removed and stewarded over 600 boxes of government records from the Office of the Secretary of State, Department of Lands, and Office of the State Controller throughout the Capitol Restoration.

- Supported the Division of Public Works throughout the restoration with critical insights and research regarding the nature and preservation of the historic structure.

- Produced the Idaho State Capitol’s signature permanent exhibit, Governing Idaho: How People and Policy Shape Our State.

- Established temporary exhibit galleries enriching and providing context to the building and Idaho’s history.

- Worked collaboratively with artist Dana Boussard to remove and reinstall the Capitol Murals at the University of Idaho.

Idaho’s rich history is featured in a collection of reproduction historic photographs, curated especially for the Capitol by the Idaho State Historical Society. These are displayed in committee rooms and legislative spaces throughout the capitol. These photos can be yours as well!

Search the digital catalog linked below to select the images you would like to reproduce.

Image Catalog for Idaho Statehouse

Click the link below for the photo ordering packet; this will include reproduction and use policies, price lists and order forms.

Forms are accepted as e-mail attachments or can be mailed to the Idaho State Archives: 2205 Old Penitentiary Road, Boise, ID 83712.

To discuss photographic image reproduction orders please call (208) 334-2620 or e-mail us.

Fees for commercial use and research services support preservation and access to Idaho’s historical archives.