Governor John Evans initially appointed the Governor’s Lewis and Clark Trail Committee in 1983 to assist state agencies, the legislature, and Idaho communities in better preserving and promoting the portion of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail that lies in Idaho.

Governor Phil Batt expanded the size and scope of the committee in 1995 to oversee Lewis and Clark Bicentennial activities in Idaho. Following the bicentennial, Governors James Risch, Butch Otter, and Brad Little reauthorized the committee with the goals of preserving pristine Lewis and Clark trail properties, the development of interpretive centers, the education of thousands of Idaho students, and awarding millions of dollars to Idaho communities to help them tell and preserve the Lewis and Clark story in Idaho.

Governor Little’s Executive Order continuing the committee also added the following responsibilities:

- Coordinate activities and partner with federal, state, local, tribal, and private organizations to protect the trail and promote responsible use of the trail.

- Advise the Office of the Governor, the Idaho State Legislature, the Idaho Congressional Delegation, Idaho commissions, bureaus, agencies, and committees regarding activities and policies that relate to the trail and the history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

- Promote educational opportunities about the trail through financial support and technical assistance.

- Sustain the current infrastructure and programs along the Lewis and Clark trail corridor in Idaho, many of which were initiated with the committee financial support during the Lewis and Clark bicentennial.

CONTACT US

(208) 334-2682

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

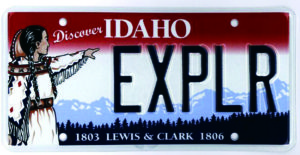

Lewis & Clark License Plate

The Governor’s Committee partners with the ISHS to administer this grant. ISHS Trustee, Hope Benedict of Salmon, serves as the liaison between the ISHS and the committee. The award is funded by proceeds from the sale of the specialty Lewis and Clark license plate (commonly known as the Sacajawea license plate). By Idaho statue, ISHS maintains this license plate money in a dedicated fund for this use.

Support Our Work: Buy a Lewis and Clark License Plate

The sole source of funding for the Governor’s Lewis and Clark Trail Committee comes from proceeds of the specialty Lewis and Clark license plate. Idaho residents may purchase these handsome plates for their vehicles. For decorative purposes, anyone may purchase a personalized souvenir plate, which also make excellent gifts. For information on ordering vehicle or souvenir license plates visit the Idaho DMV. Click on “Order Personalized/Sample License Plates,” and continue to the Lewis and Clark plate under “State Symbols and History.”

The Lewis and Clark Trail in Idaho is a National Historic Landmark. Your purchase or renewal of a Lewis and Clark license plate is an important contribution to ongoing efforts to preserve this national treasure and educate the public about Lewis and Clark in Idaho.

Proceeds from the specialty license plate support a diversity of stewardship and educational efforts, including:

- Ongoing support for the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Educational Center, Salmon

- Ongoing support for the Weippe Discovery Center, Weippe

- Ongoing support for annual Lewis and Clark Trail cleanup and stewardship projects

- Ongoing support for the Lewis-Clark State College “Lewis and Clark and the Nez Perce Speakers Bureau,” which sends dynamic programming to schools and organizations statewide

- Educational programs

- Publications

- Interpretive projects

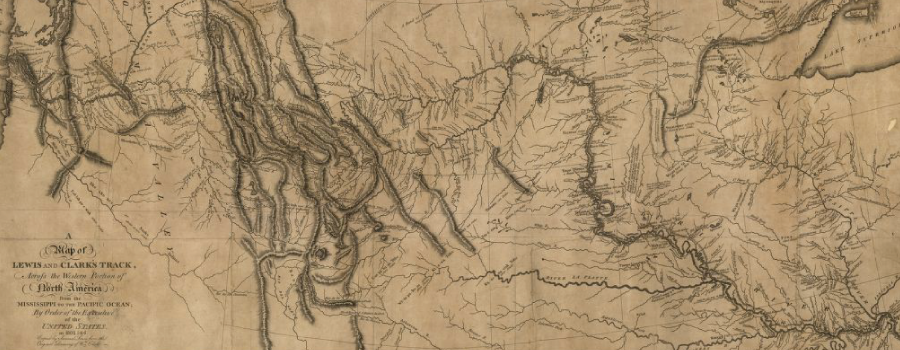

An Overview of the Corps of Discovery

Meriwether Lewis and three of the expedition’s best men entered what is now Idaho on August 12, 1805 at Lemhi Pass. They were out in advance of the main expedition because canoes could go no further up the narrowing headwaters of the Missouri River. Horses were needed or the expedition would surely fail, so Lewis desperately searched for Native Americans who might trade for those horses. Fortune smiled the next day when his party met Chief Cameahwait and the Shoshones.

One of the “miracles” of the expedition was that Cameahwait turned out to be Sacajawea’s brother. This helped relieve the Indians’ fears that the strangers might be enemies and it made trading for horses much easier.

Captains Lewis and Clark hoped there would be easy river passage to the Pacific once they crossed the Continental Divide. Instead, they were sorely disappointed when they saw range after snowy range of mountains spreading endlessly to the west. Still, they didn’t give up on the river idea. Their new Indian friends told them it was not possible to make canoes and travel the Salmon River because of rapids and narrow passages. Clark thought they were exaggerating, but not after he made a side trip of about 12 miles down what we now call “The River of No Return.” His observations of the wild river clinched the decision to cross the mountains on horseback and foot, with one of the more well-traveled Shoshones, Toby, as their guide.

The expedition struggled across Lost Trail Pass and down the Bitterroot River from present-day Sula (where they fortunately met a band of friendly Salish Indians) to Lolo, Montana. There Toby showed them the eastern terminus of what the Nez Perce called their Trail to the Buffalo. We call it the Lolo Trail, but for centuries it was the way the Nez Perce on the west side of the mountains travelled eastward to rendezvous with their Salish friends and hunt buffalo. The expedition rested for nearly two days at appropriately-named Traveler’s Rest and then began a 9-day ordeal crossing the Bitterroot Mountains. The party re-entered what is now Idaho at Lolo Pass before descending to the Lochsa River where Toby’s people had sometimes gone to fish. But that wasn’t the route to Nez Perce Country, so to get back on the trail, the expedition slipped and slid through an early snow fall up a steep slope we call Wendover Ridge. After struggling for nearly 12 miles, they were at the top and again on the Lolo Trail. Food was scarce, they were all wet and cold, and the end of the dismal, confusing mountains was nowhere in sight. Again, desperation set in, so Clark and six of the best hunters moved ahead of the rest of the expedition. After killing a stray Indian horse and hanging it in a tree to feed the hungry expedition when it came along, Clark emerged from the forest onto the Weippe Prairie on September 20. There they met friendly Nez Perce and were joined by the rest of the party two days later. The Indians provided food and information about the route ahead all the way to the Pacific. The photo above shows trailfinder/researcher Steve Russell describing a segment of the Lolo Trail to a group of teachers.

Despite some serious illness that affected most of the men, canoes were constructed on the banks of the Clearwater River near present-day Orofino. The expedition then left their horses with the Nez Perce, buried their saddles, and became water-borne in five dug-out canoes on October 7. They passed by the confluence of the Snake River at what is now Lewiston on October 10, leaving Idaho and moving on to the “Western Sea.”

After a miserable, wet winter at Fort Clatsop in western Oregon, the captains finally gave up on meeting a hoped-for sailing ship that might take them home. Instead, they travelled by canoe and then horseback up the Columbia River and re-entered Idaho on May 5, 1806. They retrieved their horses and saddles and set out to re-cross the Bitterroots. To their disappointment, they soon found that deep snow blocked their way.

Again, the Nez Perce became their hosts and the expedition settled in at what we call Long Camp just across the river from Kamiah. During the month-long wait for snow to melt in the mountains, the men traded, played games and held races with the Indians. Captain Lewis collected plants and wrote about the bears, birds, toads and other natural features of the area, helping to fulfill his charge from President Jefferson to document all that was found by the “Corps of Discovery.” In fact, about one fourth of the plant specimens Lewis took back to Virginia came from this long stay at Kamiah. The captains also practiced their doctoring skills, often winning the gratitude of suffering natives.

During the encampment, Sergeant Ordway and two privates were sent overland through the country around present-day Grangeville and Cottonwood to the Snake River. Salmon had arrived there and not at Kamiah, so the captains thought it would be a short trip to acquire some from the Indians along the river to help feed the men. The anticipated half-day trip turned into a week-long ordeal across steep mountains. When the men returned, it was with very few fish and the catch was already rotting!

The long wait at Kamiah ended on June 10 and the expedition made its way up the hillsides to the Weippe Prairie. The prairie shimmered like a lake with blue camas in bloom. But snow still blocked the passage to home and a succession of attempts ended in more waiting. At one point, the men cached their baggage part way up a mountain beyond Hungery Creek and did what Lewis called the only “retrograde march” of the entire journey. The captains also came to realize that they needed Indian guides to take them across the confusing mass of mountains that we call the Bitterroots. Remains of the ancient, native trail is still visible in some places, as depicted in the photograph to the right.

With the help of young Nez Perce men and the snow frozen enough to bear the weight of horses, the expedition finally made it across the mountains. Their last night in Idaho was spent near today’s Powell Junction. The next day, June 29, 1806, Lewis happily “bid adieu to the snow” and the expedition ended the challenges of Idaho with hot baths and a joyous camp at Lolo Hot Springs in Montana.