Serving the Nation, Representing Idaho: Honoring 250 Years of America's Military History

As the United States approaches the 250th anniversary of its founding in 2026, Americans have the opportunity to reflect on the enduring ideals of the American Revolution—equality, liberty, and justice—and honor the legacy of the US Army and the sacrifice of servicemen and women from every state, including Idaho. On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress created the Continental Army, the foundation of today’s US Army, in response to the growing unrest near Boston, Massachusetts. A day later, on June 15th, that same body of delegates nominated and selected George Washington to serve as Commander-in-Chief, shouldering the immense responsibility of transforming volunteers, many of them farmers and tradesmen, into a disciplined force capable of fighting against the British Army. Between June 1775 and July 1776, when the Continental Congress drafted the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Army experienced defeats and victories across the colonies of Massachusetts, North and South Carolina, Virginia, and into Canada. Honoring and recognizing these early battles of the American Revolution, and the lives lost and relationships between families and friends shattered over differing opinions on independence, is important in the lead up to the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. But so, too, is looking at how the American Armed Forces, more generally, have always fought to protect our American experiment, and the citizens and residents of this country. In telling that story, Idaho’s servicemen and women become central players in this important story.

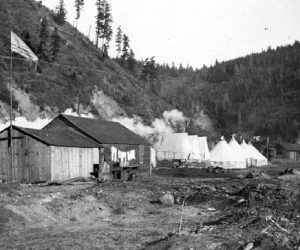

George Washington faced numerous challenges throughout his tenure as Commander-in-Chief. The Continental Congress provided limited funding and supplies to the new army, which by extension meant that the earliest American troops often faced rough conditions. However, surviving these grueling hardships would come to define the character of American military service for generations to come. Enlisted men began their days before dawn with meager breakfasts, followed by long hours of marching, drilling, and manual labor such as foraging for food, chopping firewood, and building fortifications. They carried heavy loads, including muskets, knapsacks, and other personal items, often enduring poor clothing and worn-out boots, sometimes without proper footwear. Moreover, camp conditions challenged soldiers with overcrowding, poor sanitation, and inadequate shelter that contributed to disease outbreaks and widespread hardship. During the infamous winter at Valley Forge, shortages of clothing and shoes made conditions extremely difficult. Despite these hardships, the Army’s perseverance at pivotal battles such as Trenton, Princeton, and Yorktown turned the tide of the war, securing independence and establishing the Army as the nation’s first enduring institution.

After the Revolution, the Confederation Congress disbanded the Continental Army, reflecting the new republic’s wariness of standing armies; however, persistent threats on the frontier and from foreign powers soon necessitated the creation of a small professional force—the United States Army— which Congress authorized on June 3, 1784. The “First American Regiment’s” presence on the frontier, particularly in the West, brought it into direct contact—and often conflict—with Native Americans. Campaigns like the Nez Perce War of 1877 in what would become Idaho reveal the complexity of American expansion, as soldiers and settlers pressed into new territories, forever altering the lives of Indigenous peoples and shaping would become the Gem State in 1890.

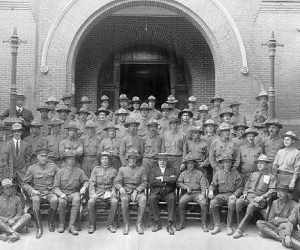

Idaho’s military tradition began during the territorial period, when volunteer militia companies formed in the 1860s to address conflicts between early settlers and Native American populations. A more formal territorial militia existed from 1877 to 1879. However, it dissolved as the need for a localized military presence and the threat to settlers diminished with the implementation of federal Indian policies. By 1889, during Idaho’s constitutional convention, delegates mandated the creation of a permanent militia, leading to the organization of the First Regiment of Idaho Infantry in 1890, with the official establishment of the Idaho National Guard occurring on March 14, 1891, via legislative action. This momentous action fulfilled a constitutional requirement and signaled Idaho’s commitment to service and defense, anchoring the state’s identity to the nation’s military story.

The Spanish-American War in 1898 marked the Idaho National Guard’s first major federal activation and entry into the broader narrative of American military expansion. The Philippines received Idaho troops, who distinguished themselves in several engagements, including the battles of Santa Ana and Caloocan. Twenty-three Idahoans died during this campaign, and monuments on the capitol grounds in Boise commemorate their sacrifice, testifying to the state’s enduring reverence for military service.

The twentieth century brought new challenges and opportunities for Idaho’s citizen-soldiers as the nation faced global conflicts defining the modern era. The federal government mobilized the Idaho National Guard again in 1916 during border disputes with Mexico and deployed units to Nogales, Arizona, before mobilizing them for World War I. World War II saw the military mobilize Idaho Guard units for service in the Pacific and European theaters, with the 148th Field Artillery Regiment deploying to the Philippines. The establishment of major installations such as Gowen Field Air National Guard Base in Boise and Mountain Home Air Force Base during this period expanded Idaho’s military significance and brought new communities into the fabric of national defense.

Throughout the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the Guard has responded to state emergencies, natural disasters, and civil disturbances while supporting presidential inaugurations and significant national events. In recent decades, Idaho’s military personnel have participated in the Gulf War, Kosovo, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with the Idaho Air National Guard’s A-10 aircraft and personnel playing significant roles in close air support and humanitarian missions. Today, the Idaho National Guard consists of more than 3,000 soldiers and 1,300 airmen, with a presence in nearly two dozen communities across the state. As the nation commemorates the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and the Army’s founding, Idaho’s military legacy is a testament to the enduring values that have shaped the American experience. And through initiatives such as “Tell Us Your Story,” the Idaho State Historical Society invites Idaho’s military and National Guard families to share their personal and family experiences, ensuring that the state’s military history is preserved for future generations. These efforts not only honor the sacrifices of Idaho’s soldiers but also reinforce the values of equality, liberty, and justice that have defined the American experience.

Written by HannaLore Hein

Bibliography

Idaho Military Division. “Our History.” Accessed June 17, 2025. https://www.imd.idaho.gov/idaho-national-guard/our-history/.

Idaho Military Historical Society and Museum. “Pass in Review: The Official Newsletter of Idaho’s Military Historical Society and Museum.” Summer 2019. https://museum.mil.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/IMHS-Newsletter-Summer-2019-Final.pdf.

U.S. Army Center of Military History. “An Overview of The U.S. Army Center of Military History.” Accessed June 17, 2025. https://history.army.mil/html/about/overview.html.

U.S. Army Center of Military History. “U.S. Army Center of Military History.” Accessed June 17, 2025. https://history.army.mil.

U.S. Army Center of Military History. “U.S. Army Center of Military History.” Accessed June 17, 2025. https://www.army.mil/armyhistory.

Stewart, Richard W., general editor. American Military History, Volume I: The United States Army and the Forging of a Nation, 1775-1917. Army Historical Series. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2005. https://www.history.army.mil/books/AMH-V1/index.htm.

U.S. Government Publishing Office. Army History & Heritage 2025. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2025. https://bookstore.gpo.gov/products/army-history-heritage-2025.

Army Historical Foundation. “Army History Center.” Accessed June 17, 2025. https://armyhistory.org/army-history-center/.

National Archives. “Military Resources: Military History.” Last modified June 20, 2014. https://www.archives.gov/research/alic/reference/military/american-military-history.