Illuminating Idaho Member Newsletter

Illuminating Idaho is the Idaho State Historical Society’s exclusive member newsletter, created just for history lovers like you. Each month, it shines a light on fascinating stories from Idaho’s past, highlights statewide historical happenings, and shares unique ways for members to get involved. It’s your inside connection to the people, places, and moments that continue to shape the Gem State.

Contact

(208) 334-2682

This Month's Illuminating Idaho

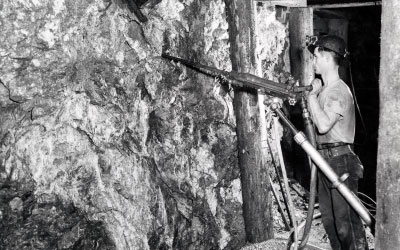

Idaho's Mining Labor Strikes: Conflict and Confrontation

written by state historian hannalore hein

Instances of labor unrest are familiar chapters throughout US history. In the late 19th century, north Idaho’s mining communities were the stage for intense labor conflicts that shaped the state’s history and the broader labor movement in America. These conflicts culminated in three significant confrontations in 1892, 1894, and 1899, each requiring federal military intervention, and highlighted the struggle between workers fighting for better conditions and mine owners determined to keep control.

The Idaho mining strikes were part of a larger pattern of labor unrest in the American West during this period. Similar conflicts occurred in other mining regions, such as Colorado and Montana. These events reflected the growing pains of industrialization, as workers sought to improve their conditions while companies strived to maintain profitability and control. The strikes also highlighted the complex role of government in labor disputes. While authorities often sided with mine owners initially, the extreme violence and property destruction eventually forced intervention, sometimes to the benefit of the striking workers.

The troubles began in earnest in 1892. As mining corporations sought mineral wealth, workers’ unions fought for recognition, better wages, and improved working conditions. Company efforts to break strikes by importing strikebreakers and using armed guards provoked violent reactions from the miners. The Western Federation of Miners (WFM), formed in 1893, emerged as one of the most militant labor organizations of its time. With 50,000 members across 200 union locals by 1902, the WFM alarmed mine owners, who formed Mine Owners’ Association to counter union efforts.

The 1892 clash began when mining companies announced wage cuts. Miners walked off the job on June 1, leading to a lockout and the importation of strikebreakers. As violence escalated, Idaho Governor Norman B. Willey proclaimed on June 4, warning of military intervention if the unrest continued. The situation reached a boiling point on July 11. Miners attacked two local mines using gunfire and dynamite. The fighting resulted in six deaths and the capture of 150 non-union workers. This sudden outbreak caught company, local, and state officials off guard. Governor Willey, realizing the gravity of the situation, appealed to President Benjamin Harrison for federal troops. Harrison initially hesitated but eventually agreed to send in the military.

The Army’s involvement in the Coeur d’Alene disturbances raised serious questions about the neutrality of state and federal officials. Critics saw it as a partisan use of federal forces to break strikes. However, the government had a long history of using troops to maintain order, dating back to the Whiskey Rebellion of the 1790s. The president could deploy federal forces to protect states from violence, enforce federal laws, and safeguard citizens’ civil rights.

The Coeur d’Alene conflicts highlighted the complex relationship between labor, capital, and government in the late 19th century. State officials, recognizing Idaho’s economic dependence on mining, often allied with mine owners against the unions. These events set the stage for further confrontations in 1894 and 1899, requiring federal intervention. The conflicts in the Coeur d’Alene region symbolized the broader struggle between labor and management in the American West. The use of federal troops in these labor disputes remained controversial. To labor advocates, it represented an abuse of power and a tool for strikebreaking. To mine owners and state officials, it was a necessary measure to maintain order and protect property.

As the 20th century dawned, the Coeur d’Alene mining wars stood as a stark reminder of the tensions that could arise when labor rights, corporate interests, and government authority collided. The labor conflicts proved the power of organized labor, the lengths to which both sides would go to achieve their goals, and the evolving role of government in mediating industrial conflicts. These historical events continue to resonate today, reminding us of the importance of labor rights and the potential for conflict and progress in industrial relations.[i]

Laurie, Clayton D. 1993. “The United States Army and the Labor Radicals of the Coeur d’Alenes: Federal Military Intervention in the Mining Wars of 1892-1899.” Idaho Yesterdays 12-29.

Captivating Conversations: Legends and Legacies

EVENT DETAIL-

00

days

-

00

hours

-

00

minutes

-

00

seconds