National History Day in Idaho

National History Day In Idaho (NHD) is a year-long student-led academic program focused on historical research, interpretation, and creative expression for 4th-12th grade students across Idaho. By participating in NHD, students become writers, filmmakers, web designers, playwrights and artists as they create unique contemporary expressions of history. The experience culminates in a series of competitions at the local and state levels and an annual national contest in June.

Students who participate in NHD build skills that are key to success in college, career, and citizenship. NHD teaches critical thinking, writing, and research skills. They learn to speak publicly, collaborate with team members, communicate ideas effectively with diverse audiences, manage their time, and persevere through challenges.

Teachers create an inquiry-based classroom where they guide, direct, and coach toward student achievement. Teachers have the flexibility to adapt the program to meet the needs of their classroom. Teachers guide students through the process of learning how to learn and making informed conclusions coming to understand. Studying the stories and history of our local communities, states, nation and the world broadens not only this global view, but also builds empathy and understanding of cultures, conflict, and resolution.

Contact

(208) 780-5190

Thank you to our National History Day In Idaho sponsors:

Bates Family Foundation

The College of Idaho

Nagel Foundation

Receive National History Day in Idaho Updates

Are you a student or educator interested in receiving more information about the National History Day In Idaho contest? Submit your information below and a National History Day In Idaho Coordinator will reach out to you soon!

If you are interested in information about judging or volunteering, please visit this page: history.idaho.gov/nhdi/volunteer

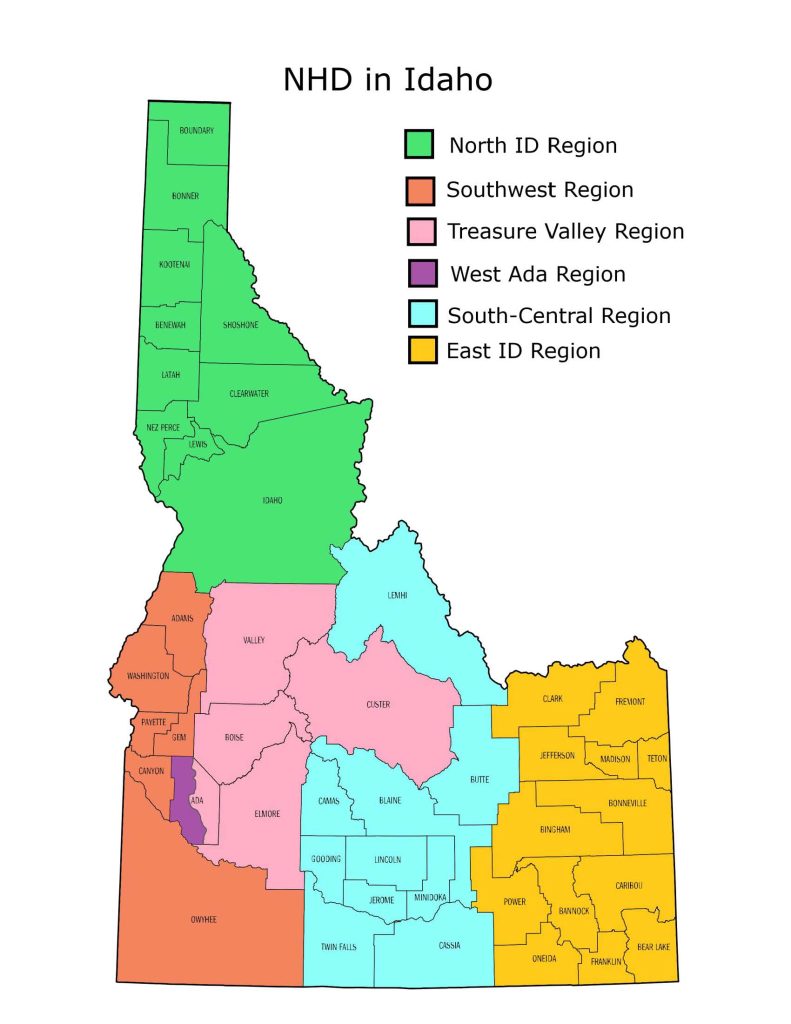

NHDI Contest Calendar

NORTH: February 14, 2026, 1912 Center, Moscow

VIRTUAL REGION (STATEWIDE)*: Week of February 16, 2026, Online

TREASURE VALLEY & SOUTH-CENTRAL: February 21, 2026, South Junior High School, Boise

SOUTHWEST: February 25, 2026 (weekday evening), Caldwell High School, Caldwell

EAST: March 2, 2026, Rocky Mountain Middle School, Idaho Falls

WEST ADA: March 7, 2026, Renaissance High School, Meridian

STATE CONTEST*: April 4, 2026, The College of Idaho, Caldwell

NATIONAL CONTEST: June 14-18, 2026, University of Maryland, College Park

Frequently Asked Questions

During the school year, Idaho students create one of the five types of projects (historical paper, documentary, performance, exhibit, or website) and register to compete at the local level. Local winners then can move onto the state contest to compete with students from all across Idaho. State contest winners have the opportunity to compete at the national level with peers from all over the country. Visit https://www.nhd.org/ for more information about the National Contest.

Students gain academic and real-world skills through this project. According to the 2011 National Program Evaluation, NHD students already know how to do college-level research by digesting, analyzing, and synthesizing information. This aids students not just in humanities classes but gives them skills that are multi-disciplinary. Students also gain oral communication and presentation skills, collaboration, time management, problem-solving, and perseverance.

Students have a unique experience in a competition against their peers. They get to be proud of their hard work, and research topics that are important to them, and practice communicating in a medium that they enjoy!

Students grades 4th -12th are able to participate. All types of schools are invited to join: public, private, charter, or homeschool.

4th and 5th graders participate in our Youth division and winners can move on to the State Competition.

6th – 8th graders participate in the Junior Division.

9th – 12th graders participate in the Senior Division.

Junior and Senior division and category winners move on to the National Contest in June.

One of the advantages of participating in NHD is that it can be adapted to each classroom! Using the resources available, teachers can guide students through creating a project in a way that meets their class learning objectives and is flexible for their schedule. Students create projects during the school year in preparation for a series of contests in the spring (February – April).

The 2025-2026 theme is: Revolution, Reaction, Reform in History. (NHD Theme Website)

Read through the NHD Rule Book available on the NHD website. The National Office also provides a Theme Book on their website explaining the annual theme and ways to interpret it.

The NHD website also has excellent resources for teachers including curriculum, example projects, tips and tricks, tutorial videos, project examples, and project checklists for students. You can find those resources here: https://nhd.org/en/teacher-resources/

Check out our activities, worksheets, and curriculum available here! NHDI Resources

Sign up for our mailing list and keep checking your inbox. We will be sending out resources, information, and opportunities for NHD teachers.

The success of the local and state contests is largely thanks to the volunteers and donors that support this project! There are several ways to help; we are looking for volunteers to help with our contest days. This ranges from event coordination, set-up, take-down, and assisting during the contests. Another way that we support and encourage our students is by offering special awards for specific project types. Please e-mail NHDidaho@ishs.idaho.gov for more information.

Students can participate in NHD as independent students! This is a big project and you will need to keep yourself on task outside of school, so be sure to pay attention to this website for all the important deadlines.

Your parent or guardian should sign up for our email list at the bottom of this page to receive all future information. Every student needs to have an NHD teacher when they register their project for a contest, so your parent or guardian will fill this role for you.

Also, be sure to read through the answer for “I’m a teacher…” in this FAQ section, along with your parent or guardian. You’ll see lots of links for helpful resources that will help you through the process.

Lastly, please e-mail NHDidaho@ishs.idaho.gov with any questions.

Histor-E Lessons

Of all the notable figures in Idaho’s history, Polly Bemis stands out as one of the most resilient and memorable. Polly Bemis was born in northern China in 1853. In 1872, she was smuggled to the United States and sold as an enslaved person in San Francisco for $2,500. From San Francisco, Bemis was escorted to Portland, Oregon, and eventually settled in Warrens, Idaho Territory (now Warren) with her Chinese owner. Polly earned a reputation in the small community for her clever, pragmatic, and kind personality. While it is uncertain how Polly eventually acquired her freedom, a census shows Polly living with her future husband, Charlie Bemis, in the mid-1880s. Charlie had called Idaho home since roughly 1866 and made a name for himself in Warren as a merchant, miner, saloon owner, and boarding house operator.

Charlie and Polly formed an intense bond. It’s been noted that Charlie often saved Polly from harassment at the saloon. Polly returned the favor by nursing Charlie back to health after he was shot in the face following a disputed poker game. Polly would again save his life when their home caught fire in 1922. Polly and Charlie married on August 13, 1894, in their home, which was also Charlie’s saloon. The couple soon filed a mining claim along the Salmon River near Warren, where they mined and established a small farm. Polly grew an array of fruits and vegetables and raised chickens, ducks, and cows. Polly was known to sew, crochet, and fish in the nearby river.

Polly and other Chinese immigrants of her time were never considered American citizens due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and its extension, the Geary Act of 1892. The legislation prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers. It also required Chinese immigrants to apply for a certificate of residence and always carry it with them if they wished to stay in the United States. In remote Warren, Polly had been promised assistance in filing for her certificate by George Minor, an IRS collector. Minor failed to make the journey due to impassable winter roads leaving Polly at risk of deportation. In 1896, Polly and roughly fifty other Chinese migrants appeared in the Moscow district court to petition for their certificates. She was successful and lived in Idaho until her death in 1933.

By 1920, Charlie’s health had steadily declined. He passed away shortly after suffering severe burns in the fire that destroyed their Salmon River home. Polly returned to Warren, and with the help of friends, she rebuilt their home and lived along the river by herself for over a decade. Later in life, Polly left the Warren area and was often amazed by the glimpses she got of bustling towns and cities. Regional newspapers reported Polly’s wonder at seeing a railroad for the first time, riding in a car, and even watching her first movie. Weeks after a stroke, Polly died on November 6, 1933, at the age of 80.

The National Park Service listed the Polly Bemis Ranch in the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. The 26-acre property is surrounded by 2.2 million acres of the Frank Church Wilderness Area, the largest protected wilderness area in the continental United States. During her lifetime, Polly Bemis was respected for her welcoming, bright, and mischievous personality. Today we also see her story as one of true Idaho resilience.

Written by Nicole Inghilterra and Mark Breske

The Nez Perce War stemmed from an escalating land conflict between several bands of the Nez Perce Tribe and the United States government. The 1863 Treaty, known as the ‘Thief Treaty’ by the Nimiipuu, outlined the conditions that would eventually lead to an all-out war between the Nez Perce and the US Army in 1877. The treaty era for the Nez Perce began in 1846 with the creation of Oregon Territory. Westward expansion immediately made land in the northwest more of a commodity, so much so that in 1855, territorial governor Isaac Stevens met with tribal representatives to negotiate the tribe’s surrender of 7.5 million acres of land in exchange for hunting and fishing rights. The US Senate ratified the treaty in 1859.

When gold was discovered along the reservation’s boundaries in 1860, the US government drafted another treaty to further shrink the reservation by absorbing another five million acres of reservation lands, which became the 1863 Treaty. By 1869, reservation lands were reduced to just 750,000 acres in Idaho Territory. All Nez Perce members were ordered to move onto smaller reservation land east of Lewiston. Many tribal members defied the order and remained on their lands.

Disputes between white landowners and tribal members continued to escalate. In May 1877, General Otis Howard ordered non-treaty tribal members to move to the reservation within 30 days. By June, 600 Nez Perce members gathered on the Camas Prairie, where warriors began war ceremonies. Warriors then acted against four white men in a raid. Chief Joseph and his brother Ollokot arrived at the camp the next day to find out what had happened. Joseph knew an attempt at peace was futile at this point as General Howard moved 130 men to the reservation to retaliate. The military underestimated the power of the Nez Perce and was defeated in the Battle of White Bird Canyon on June 17, 1877, thus beginning the Nimiipuu’s escape eastward from US soldiers. A small band of Nez Perce warriors slowed military efforts amidst the retreat from Idaho into Montana Territory. Brigadier General Nelson Miles led a surprise attack on the Nez Perce camp on the morning of September 30. On October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph surrendered at the Bear Paw battlefield in Montana Territory with one of the most infamous speeches in US history:

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzoote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say, “Yes” or “No.” He who led the young men [Ollokot] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are — perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.

Instead of returning to Idaho as promised during surrender negotiations, General William Tecumseh Sherman ordered the remaining tribal members to be sent to Kansas. First, captives began their 265-mile trek east to the Tongue River Cantonment on October 23, 1877. On November 23, the remaining prisoners left for Fort Leavenworth by train, along with their lodging and provisions.

In 1879, Chief Joseph made one final plea to President Hayes and US Congress in Washington DC to return to Idaho. The government did not grant Joseph’s wish, and he and the Nez Perce were sent to Oklahoma, establishing a small reservation near Tonkawa. In 1885, Joseph and his 268 surviving tribespeople returned to the pacific northwest, settling at the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington. Chief Joseph died there in 1904 at the age of 64. He was revered, even by his adversaries, as a humanitarian, peacemaker, and diplomat.

Written by Mark Breske

The 1892 Coeur d’Alene labor strike stemmed from a dispute between mining companies and railroads over increased rates for hauling ore amidst a national decline in prices for lead and silver. The introduction of boring machines reduced the need for laborers in those positions, forcing them into lower-paying jobs. Mine owners reduced wages and increased work hours to offset increased costs, deepening the rift between union workers and mine owners. In 1892, miners began to strike against the unfair wages and hours. When union miners walked away from their jobs, mine owners recruited replacement workers by rail from surrounding states to maintain operations. Union miners often confronted the replacement workers upon their arrival, even threatening violence if they chose to work.

Silver-mine owners hired undercover Pinkerton detective agent Charles Siringo to infiltrate the union and gather information about their activities to combat the increase in hostility and slow the union’s momentum. Siringo joined the Gem Miners’ Union under the identity “Charles Leon Allison.” The union appointed him as recording secretary, which gave him access to all the union’s records. Siringo would then report back to his employers, which subsequently foiled several attacks and sabotage efforts by union workers. He was eventually suspected as a spy when the Mine Owners’ Association newspaper published information unknown to those outside the union circle. In fear of retribution, mining companies hired armed guards to patrol mining grounds while union miners began assembling.

On July 11, 1892, union members opened fire on guards and workers at the Frisco mill. Siringo had warned of a standoff, so guards were somewhat prepared for the ambush—equipped with Winchesters behind barricades. Nevertheless, a three-and-a-half-hour standoff ensued. Finally, striking miners loaded a Union Pacific railroad car with 750 pounds of giant powder. They sent it down the track toward the mine, destroying the mill and reportedly killing twenty union men before taking several captives. Shortly after the explosion, hundreds of union strikers closed in on the mining town of Gem, where a similar gunfight broke out, resulting in three deaths per side and 150 more strikebreakers and guards held captive at the union hall. Siringo narrowly escaped through a hole in the barracks floor and fled to a nearby wooded area.

Later that same evening, five hundred union strikers boarded a train to Bunker Hill mine. Strikers swiftly overpowered staff at the mine before placing explosives beneath the ore mill. The next morning, union miners gave the manager an option to vacate the mine with all staff, or they would blow up the mine. The mine’s manager “hastily discharged” three hundred non-union men from the site, seventeen of whom suffered injuries from gunfire while waiting to board a boat at Lake Coeur d’Alene.

Governor Willey declared martial law and deployed six companies of the Idaho National Guard to end the violence. Federal troops also aided in ending the standoff, detaining over six hundred miners. Siringo emerged from hiding and identified union leaders and suspects in the attack, which led to eighteen convictions, including George Pettibone, who prosecutors later linked to the 1905 bombing assassination of former Governor Frank Steunenberg. Martial law and the Coeur d’Alene military occupation lasted until November 18, 1892. Eventually, the mines were re-opened, and union miners were re-employed.

While the 1892 Coeur d’Alene labor strike was not the end of labor disputes between mine owners and union workers, the events inspired the founding of the Western Federation of Miners in 1893, which sought to outlaw hiring labor spies. The union also moved to pay fair wages relative to job danger, ensure preferential employment of union men, and repeal conspiracy laws against unions. The union was viewed as conservative and economically focused, seeking change through “education, organization, and legislation,” a stark contrast to the violent movement that sought to incite change just one year prior.

Written by Marketing and Communications Officer Mark Breske

From the community’s labor of cattle drives, mining, railroads, and agricultural impacts to the leadership of important public figures, Hispanic Idahoans are essential to Idaho’s development, one of the most economically proficient, environmentally focused, and safest states within the U.S.

Hispanic heritage in Idaho pre-dates statehood and has been present in every facet of life. Spanish and Mexican immigrants lived off the land as itinerant trappers and hunters in the Boise Valley as early as 1860. Before the railroad arrival around 1868, Mexican vaqueros/cowboys from Mexico and the Southwest were instrumental in bringing the cattle to Idaho ranches from Texas, California, and Colorado. They left Mexican-Spanish vocabulary; places like mesa and corral, tasks like rodear, darse vuelta/dally up, items like reatas, mecates, stirrups, and many more. They also left the western style of dress that persists today.

After gold was discovered in the Boise Basin in 1862, many vaqueros transitioned to mining and mule packing. Many more Mexican laborers arrived bringing with them skills that were essential to the development of Idaho’s mining industry. As miners, Latinos developed mining districts and as mule packers, they became the lifeline of remote mining towns by providing them with merchandise and goods. They left place names such as Orofino, Alturas, and Esmeralda.

This influx took shape in cultural hubs throughout the state. One of the most influential examples first emerged at 115 Main Street in Boise. In the 1860s, vaquero and local herder Antonio de Ocampo rented part of Boise’s Block 29 on Main where Mexican laborers stayed while in Boise. He welcomed muleteers like Jesus Urquides and Manuel Fontes to name a few. De Ocampo later bought this parcel of land that had become known as Spanish Village. The village served as an ethnic center for the Spanish-speaking population and after De Ocampo died in 1878 the land ownership transitioned to his good friend, Jesus Urquides.

Jesus Urquides belonged to a remarkable generation of Mexican mule packers found thorough the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. He was born in Sonora Mexico and arrived in California during the Gold Rush Era. With the shift in mining to Nevada in the 1850s, Urquides began to pack over the Sierra Nevada. Later he transferred his operations to Walla Walla, Washington and from there to Lewiston, Idaho. In 1963, he packed thirty-two mules to Boise. Already a shrewd, and calculating businessman, he no doubt figured that Boise had a future.

Urquides utilized his business acumen in Idaho. He transferred his operation to Boise and began supplying local miners with food and supplies. When in 1978, he inherited the piece of land in the outskirts of Boise from his good friend Antonio de Ocampo, Urquides built some stables and corrals to accommodate his outfit and his freight business was formally established! Boise’s Spanish Village became a hub of Hispanic culture.

Jesus Urquides’s contributions to what was little more than a ‘frontier boomtown’ helped establish Boise as a flourishing community within Idaho. He died in 1928 and his daughter Dolores “Lola” Urquides Binnard continued renting out the cabins and giving tours for tourists, keeping her father’s legacy alive. By 1956, Spanish Village had roughly 20 tenants and after Dolores passed away in 1965, the buildings fell in disrepair and became a sore spot. It was demolished in 1972 and an important part of Idaho history was destroyed. During its sesquicentennial, the city of Boise established a memorial where the Spanish Village once stood to honor Urquides’ legacy.

Around the turn of the century, massive government irrigation projects enabled Idaho farmers to grow marketable agricultural produce. Working in tandem with developers, the railroad companies sought to expand their markets by bringing settlers to the desert and shipping their crops to markets. Labor recruiters turned increasingly to Mexican immigrants to meet the needs of Idaho’s expanding economy: railroads and sugar beets. By 1910 a large number of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were building and maintaining the railroad system in the American West including Idaho and its railroads yards in Pocatello.

In 1917, during World War I, the Utah Idaho Sugar Company, then controlled by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, brought about 1500 Mexican workers and their families to the district of Idaho Falls, Shelley and Blackfoot to fill the desperate farmer’s needs, but failed to provide appropriate working conditions and housing and to its workers. The Mexican government complained about inhumane treatment of Mexicans in the beet fields.

In 1926, San Diego Fruit and Produce, a California company contracted with Idaho farmers on the production of fresh peas. As harvest times varied from area to area, the company brought the migrant pea workers crews who worked diligently; picking the peas in hampers and sending them to a nearby packing house where they were sorted, packed in crates and loaded into refrigerated railroad cars. In this way the peas were delivered to lucrative markets in the east coast of the United States.

In the 1930s as the Great Depression began, it was a time of economic hardship and suffering for most working people in the United States, but Mexicans suffered additional hardship of being pressured to return to Mexico whether they had been born there or not. Idaho farmers were forced to hire “white” people only, but complained that white labor could not do the work needed to be done. Still, they began fluctuating the payment per pound to the Mexican workers and to offer bonuses if certain conditions were met like staying until the end of the harvest regardless of sickness. In 1931, the Mexican Vice Consul traveled to Idaho to investigate and was able to interview workers and take photographs of the “dwellings” on behalf of the workers. The conditions and housing were deplorable.

In 1935, after a dispute about pay between the pickers and the company, the recruiters and labor contractors had offered them $1.25 for every hundred pounds of peas picked plus a bonus if they stayed till the end of the harvest. Once in Drills, Idaho, they discovered that the pay was only $0.70 cents and the bonus was $0.15 cents per hundred pounds. The summer was hot and dry. It was the second year of a severe drought and tensions mounted between the farmers of the upper and lower basin over the use of scarce water resources. The pea picking crews demanded $1.00 per every hundred pounds and when the company refused to comply, 1500 workers went on strike. The conflict escalated to which the farmers faced the prospect of economic ruin if they lost their pea crop, so the governor declared martial law and sent the Idaho National guard, arresting the leaders and forcing the workers to pick up their hampers and return to work.

Widespread Hispanic migration to Idaho increased in the 1940s due to agricultural labor shortages exacerbated by the onset of World War II. Most Anglo agricultural workers left farming for wartime industrial jobs or joined the military. With farm production threatened, the governments of the United States and Mexico established a series of agreements allowing millions of Mexican men to migrate to the United States for contractual agricultural labor. In August 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s executive order established the Mexican Farm Labor Program or the “Bracero Program,” which created many more opportunities for Mexican laborers in Idaho.

The word “bracero” is derived from “brazo,” the Spanish word for arm and its colloquial meaning is “manual laborer” or “one who works using his arms.” The Bracero Program lasted from 1942 to 1964, with approximately 4.6 million contracts issued. It allowed a bracero to enter the United States under a six or twelve-month contract primarily through agricultural contracts. Workers returned to Mexico after working in a particular region in the U.S. for an allotted time. They could sign another contract and return to the U.S. to work after completing their initial agreement. Over 15,000 Mexicans labored in Idaho through the Bracero Program, making the Gem State one of the three most significant agricultural laborer hubs during World War II, behind California and Texas.

The Amalgamated Sugar Company recruited the first permanent Mexican workers to the Twin Falls Migratory Farm Labor Camp in 1942. While it is unknown if private efforts or the Bracero Program recruited these individuals, the workers joined other migrants living within the housing facilities. By 1947, over 1,000 Hispanics worked in the Magic Valley. However, due to substandard working and living conditions, including a bracero two-day “sit-down strike” after they found out they would be paid less than their contract specified, the program came to a halt. By 1946, the Mexican Consul refused to send additional bracero workers to Idaho officially ending the program in 1948. Still, the program had created an informal migration network from Mexico to Idaho, allowing many braceros to stay in the state after their contracts expired and help grow the region’s Hispanic community. In the 1950s labor shortages continued and Mexican American families, most of them from the southern counties of Texas moved north to fill seasonal jobs. In 1957, as part of the effort to attract and retain workers, the Idaho Employment Security Agency and the Twin Falls Chamber of Commerce organized the first Cinco de Mayo Fiesta which attracted hundreds of participants. A young crew leader named Jesse Berain (who later in the 1990s became an Idaho Legislator) organized and served as master of ceremonies.

After termination of the international Bracero Program in 1964, Latino individuals and families continued to move north, with a majority migrating to Idaho by way of California and Texas. Corporations like the Amalgamated Sugar Company continued recruiting Latino laborers to work in sugar beet fields seasonally and processing plants in Nampa, Twin Falls, and Paul. Migrant workers relocated to coincide with the harvest seasons, resulting in an annual migration that developed Hispanic culture across the state. Over time, agricultural industrialization led to a decrease in seasonal labor. However, Hispanic immigration continued to rise, resulting in Latinos becoming the fastest growing population in Idaho.

Written by Ana Maria Schachtell and BSU Intern Cameron Dickie

People of Chinese descent have lived and contributed exponentially in Idaho for approximately 150 years, making names for themselves in industries and communities state-wide. While their experiences in Idaho have been far from smooth, the stories of Chinese immigrants are woven into history with rich threads. They not only took up difficult jobs, but excelled in fields such as mining, railroad construction, farming, and medicine. From Polly Bemis in Warren, to Pon Yam and Loke Kee in Idaho City, to Dr. C.K. Ah Fong and Louie Do Gee in Boise, there is a profound history of Chinese and Chinese American people in Idaho.

Some of the first Chinese people came to Idaho in the 1850s and 60s as miners and railroad workers. After the California Gold Rush, miners from all over flocked to areas like the Boise Basin, Pierce, and Idaho City. Chinese workers were restricted from claims until their white counterparts exhausted the site; nonetheless they made their fortunes from mining the remains. With construction of the transcontinental railroad wrapping up in 1869, workers settled into Idaho communities and picked up jobs in farming, cleaning, cooking, and laundry services. By the 1870s, people of Chinese origin made up almost a third of Idaho’s total population.

Most Chinese immigrants in Idaho and America were men who came over to make money for their families in China. During the 19th century, Chinese women mainly came to the U.S. unwillingly, many of whom signed binding brothel agreements they could not read. One of the most famous Idahoan women of Chinese descent was Polly Bemis. Polly’s story is fraught with myths; we do know that her struggling family sold her, and smugglers transported her to Portland. From there, she was sold to a man in Warrens (present-day Warren), Idaho, and became close friends with local saloon owner Charlie Bemis. The two married in 1894 and settled along the Salmon River, where they welcomed locals and visitors alike. Polly became known for her hospitable demeanor and called Idaho home until her death in 1933.

In the 1880s Boise boasted one of the largest Chinatowns in the Intermountain West. Chinese people settled into the community with temples (referred to as joss* houses [*pidgin for God]), laundries, gardens, restaurants, and Masonic buildings. With the limitations that came with non-citizenship, Chinese people of Idaho took up laborious work seldom recognized for its difficulty and skill. As stated by Arthur Hart, “One of the first jobs [for Chinese immigrants] …was washing and ironing clothes for whites.” Laundries in Boise dealt with constant issues of fires and wastewater disposal, but efforts to shut them down proved unsuccessful due to how heavily white households relied on their work.

From supplying individual households to local grocery stores, farms worked by Chinese immigrants prospered in the community; some Boise farms produced so much that they began to sell their crops out of state in the early 20th century. Louie Do Gee, and eventually his sons William and Tong, ran their thriving Louie Gee Garden for generations in what is now Garden City. The main thoroughfare of the city, Chinden Boulevard, combines the words “Chinese” and “garden” to pay homage to the history of the land.

Chinese restaurants served as successful ventures beginning in the 1890s until the economic downturn of the Great Depression. While not traditional Cantonese fare, the Americanized food they served grew in popularity throughout Idaho and the United States. Boise Chinese restaurants dwindled to three businesses by 1950, which was the lowest it had been since 1910. The Louies, an established Boise family since the 19th century, owned several restaurants by the 1980s, one of which, Golden Star Restaurant, continues to serve people today.

Of those who practiced traditional Chinese herbalism in Boise, Dr. C.K. Ah Fong was a well-known and beloved figurehead. All types of people frequented his business for medical assistance, and the Fong name endured in the Boise medical field for nearly a century. In 1899, Ah Fong made history as the first licensed Chinese man to practice medicine in Idaho after suing the State Board of Medical Examiners for denying him a license.

Racism and hatred played a role in the experience of Idaho, and America, for many Chinese people. In 1865, after the first Chinese miners traveled to the Boise Basin mine, the Idaho City newspaper Idaho World labelled them the “Locusts of Egypt.” The Snake River Massacre of 1887 became the worst example of violence towards Chinese people in Idaho, when an outlaw group murdered 31 Chinese people. Racist sentiments surfaced throughout the 19th and 20th centuries in the form of anti-Chinese riots, forcibly removing them from towns like Clark, Emmett, and Moscow, redirecting business to white-owned and operated companies, and the Chinese Exclusion and Geary Acts, which prevented Chinese immigration to the U.S. and American citizenship for those already living here. Boycotting Chinese owned and operated businesses as a racist measure to promote whiteness never fully succeeded due to the prominent and essential nature of work they performed. While these instances made daily life difficult for people of Chinese descent, no amount of hatred can erase their existence and contributions to Idaho.

Not all experiences were negative, however. After multiple instances of intentional harm and theft in 1890, both Boise Mayor James A. Pinney and Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson proclaimed that Chinese immigrants deserve the same rights and protections as anyone else. Generally considered a welcoming place for Chinese immigrants, Idaho City fully integrated their schools by the late 19th century. Some of the most successful businessmen of Idaho City, Loke Kee and Pon Yam, began as miners and grew to be beloved pillars in the community.

Idaho thrived as a new state because of the brave immigrants who left behind their homes for a brighter future. People of Chinese descent, both past and present, form an intrinsic part of Idaho history in a tapestry of stories. There are many more narratives of Chinese and Chinese American people of Idaho not conveyed in this article that are just as important as the stories told.

Historic sites like The Polly Bemis Ranch by Warren, The Pon Yam House in Idaho City, and the newly redone Chinese Rail Worker Memorial by Glenns Ferry offer stories for visitors to explore, while digital resources like the Idaho State Archives and Idaho Experience by Idaho Public Television offer further insights. I entreat you to pursue additional resources chronicling the Chinese people of Idaho so that we can honor their legacies and stories.

Written by Idaho State Museum Visitor Services Representative Micah Hetherington

Since gaining the right to vote in 1896, Idaho women have been involved in politics at local, state, and national levels. A new temporary exhibit at the Idaho State Archives showcases just a few of those women who have taken on the unique challenges that come with running for, and serving, in elected office as a female. Original campaign materials, historic photos, and original documents help to highlight some of Idaho’s women in government, from U.S. Legislators to County Treasurers.

Of the women featured in the exhibit, Maude Cosho stands out as a true pioneer in paving the way for women in legislature in Idaho. At a time where women were slowly transitioning into higher positions of power within state and local government, Maude’s perseverance was truly inspiring to those who followed. After her husband Harry’s accidental death in 1932, she raised three children, ran the Bristol Hotel, and served in the Idaho State Legislature (1933-34 and 1937-38). In 1931, Maude introduced the bill to give women the right to serve on juries. The four female House members (two Republicans and two Democrats) joined together in their support, but the printing of the bill was blocked, ending its possibility for passage. Maude again introduced the bill in 1933 stating, “This bill is an extension of the suffrage rights of women.” It passed the House but not the Senate. In 1937, she reintroduced it and again it failed. By the time the bill did pass, Maude was no longer in the legislature, but she did, along with a delegation of women, proudly stand behind Gov. Bottolfsen as he signed the bill into law in 1943.

Maude had quite a sense of humor too. Also, in 1931, those same four women in the House introduced the bill to make “Here We Have Idaho” the state song. When asked to stand at the Speaker’s desk and sing it, Maude retorted, “No, we want to pass the bill, not to kill it!”

During World War II, Maude joined the Women’s Army Corps at the age of 48, making her one of its oldest recruits. At age 54, she earned a master’s degree from the University of Idaho in American History. At age 57, when most people are looking forward to retirement, she began a 14-year career teaching Tohono O’odham Indian children in Ajo, Arizona. During the last two years of her life she wrote the book, “An Idaho Hodgepodge.” In her 1973 memoir she wrote, “I have done almost everything in life that I have wanted to; I am sure I could have done more if I would have tried harder.”

Learn more about Maude Cosho and other Idaho women in legislature at the Idaho State Archives. This exhibit, in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, is currently on display until March 31, 2020. It is free and open to the public during normal Research Center hours.

Written By Mark Breske and Marilyn Cosho